Is the U.S. government's quitting policy killing smokers?

Despite a growing array of FDA approved and widely used quit smoking drugs, which promised to double smoking cessation rates, on October 27,

2006 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and CDC were forced to report that the U.S. smoking rate stalled at 21% during 2005, the first year since 1997 that the rate failed to decline.

Despite a growing array of FDA approved and widely used quit smoking drugs, which promised to double smoking cessation rates, on October 27,

2006 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and CDC were forced to report that the U.S. smoking rate stalled at 21% during 2005, the first year since 1997 that the rate failed to decline.

The report casts well-deserved blame upon the tobacco industry for continuing to enslave youth and upon state legislatures for failing to adequately fund tobacco control. But the U.S. government fails to keep any of the blame for itself, although it has allowed pharmaceutical industry consultants to rewrite official U.S. cessation policy as though what's good for the industry is good for smokers.

In June 2000 the U.S. Department of Health adopted the Clinical Practice Guideline - Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, a guideline generated by a private-sector panel of experts. Guideline Appendix C openly acknowledges that 11 of the 18 experts were pharmaceutical industry consultants.

The expert panel concludes that, "Numerous effective pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation now exist. Except in the presence of contraindications, these should be used with all patients attempting to quit smoking."

These 25 words cast the U.S. government as the pharmaceutical industry's partner in promoting the mandatory use of drugs and in destroying the credibility of cold turkey. Cold turkey quitting recommendations were deleted from all government quitting literature as smokers were now told that key to quitting was to "get medication and use it correctly." State health departments have been strongly encouraged to follow suit, including being urged to make pharmaceutical quitting products available under state Medicaid coverage.

The 25 words spoke directly to hospital administrators and physicians. Doctors were forced to choose between pushing replacement nicotine on their patients or bucking the CDC, Surgeon General and official government quitting policy.

Local cold turkey quitting programs were instantly out of compliance with U.S. cessation policy. Some lost funding. All lost the backing and marketing assistance of the U.S. government. With the disappearance of local abrupt cessation programs, often the community's sole source of cold turkey quitting literature and formal ongoing support, America's cold turkey quitters now truly were on their own.

Prior to being disowned, cold turkey education, counseling and support programs generated impressive quit smoking rates that should have had experts asking how they'd compare to the extremely modest rates being generated by today's telephone quitlines, which actually discourage callers from going cold turkey. It wasn't unsual to see one-year program rates ranging from 20% to 40%. According to the evidence tables in the Guidelines themselves, historic "on-your-own" quitting rates -- without education, counseling or support - average 11.5% at six months.

If people quit cold turkey, with no support, at that rate, it follows that any product or pill that does not generate at least a 10% quitting rate at six months is somehow undercutting the quitter's own natural abilities. Clearly, HHS Secretary Michael O. Leavitt, CDC Director Julie L. Gerberding, Chronic Disease Prevention Director Janet Collins and Office of Smoking and Health Director Corinne G. Husten should not let their agencies recommend such products even if they yield billions in revenue to the pharmaceutical industry.

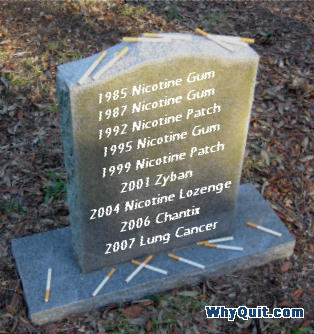

In fact, the data show that over-the-counter NRT products undercut the quitter's natural odds. Leavitt, Gerberding, Collins, Husten know or should know this. If they haven't read the full text of a March 2003 study published in Tobacco Control by two GlaxoSmithKline consultants (which makes nicotine patch, gum and lozenge products), they should. They'd learn that when you combine and average the seven over-the-counter patch and gum studies that only 7% of study participants were still not smoking at six months - a 93% failure rate.

Worse yet, they should know that most smokers have already tried quitting with replacement nicotine at least once and failed, and that repeat use of NRT brings even worse odds.

Only two studies examined second time nicotine patch use. In one, 0% of second time users succeeded (Tonnesen, Addiction, April 1993), while "Table III" in the other asserts that only 1.6% were still not smoking at six months (Gourlay, British Medical Journal, August 1995). While a failed cold turkey attempt can teach a critical lesson about the power of one puff of nicotine to destroy a quitting attempt, repeated toying with the very chemical the brain is dependent upon doesn't seem to teach anything.

It is mind boggling that government cessation policy commands that physicians prescribe, for all smokers without specific contraindications, three months of toying with either nicotine or drugs mitigating the urge to smoke, instead of allowing doctors the professional discretion to advocate the quitting method that in 1992 the CDC said was responsible for generating almost 90% of all long-term successful U.S. ex-smokers.

It is mind boggling that government cessation policy commands that physicians prescribe, for all smokers without specific contraindications, three months of toying with either nicotine or drugs mitigating the urge to smoke, instead of allowing doctors the professional discretion to advocate the quitting method that in 1992 the CDC said was responsible for generating almost 90% of all long-term successful U.S. ex-smokers.

The most troubling aspect of Leavitt, Gerberding, Collins and Husten ignoring the needs of 80 to 90% of U.S. quitters is that their online information pages continue to falsely suggest to smokers that "real-world" use of the nicotine gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray or bupropion "will double your chances of quitting and quitting for good." It simply isn't so. After more than two decades of widespread NRT use they will not be able to produce a single real-world performance survey in which those using NRT performed better than those quitting without it.

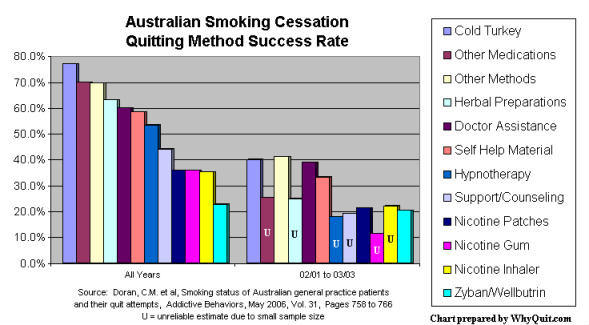

Surveys from California (2003), Minnesota (2002), Quebec (2004), London (2003), Maryland (2005), UK NHS (2006) and Australia (2006) all report absolutely no advantage for quitters using pharmaceutical quitting aids over cold turkey quitters. In fact, in the Australian study, among patients of 1,000 family practice physicians, cold turkey was twice as effective as NRT or bupropion (Zyban/Wellbutrin).

But how can this be? What about those clinical studies the government and its industry partners cite in support of their "double your chances" assertion? What Leavitt, Gerberding, Collins and Husten do not mention is that clinical NRT studies were not blind as claimed.

If they haven't read a June 2004 study by Mooney, they should. Mooney reviewed 73 allegedly double-blind NRT studies and declared that the limited number of studies assessing blindness were not generally blind as claimed because "subjects accurately judged treatment assignment at a rate significantly above chance." In other words, a significant number of study participants knew whether they were getting a drug or placebo. This knowledge makes suspect any difference in success rates.

Mooney warned researchers that, "To determine the prevalence of failure, clinical trials of NRT should uniformly test the integrity of study blinds. Moreover, if blindness failure is observed, subsequent efforts should be made to determine if blindness failure is related to study outcome and, if so, to provide an estimate of treatment outcome adjusted for blindness bias. Without these methods and analyses, the validity of NRT clinical trial results could be questioned."

The blinding analysis in a 2005 study by Dar found that 3.3 times as many placebo group members correctly guessed that they had received placebo (54.5%) as guessed that they had received nicotine (16.4%). Although the Dar study focused on smoking reduction, Tonnesen's 1993 nicotine inhaler quitting study produced strikingly similar placebo group findings in that 3.8 times as many in the placebo group correctly guessed placebo (58%) as guessed nicotine (15%). Among inhaler users, Tonnesen found that 3.5 times more correctly guessed inhaler (46%) as guessed placebo (13%), while 42% on active and 27% on placebo did not know which treatment they had received.

The blinding problem is especially troublesome because participants were recruited into clinical studies by being told that the study involved evaluation of a "medication." This recruiting pitch would naturally attract people who want chemical relief from the rising tide of anxieties and craves that their minds associated with withdrawal. For such people, assignment to the placebo group and recognition of full-blown withdrawal led to frustrated expectations.

Despite Mooney's warning that the validity of clinical studies failing to assess blindness would be subject to question, the five new varenicline studies supporting Pfizer's Chantix (U.S.) and Champix (Europe) products failed to evaluate blinding, even though placebo group blinding failure concerns were identical to those seen in NRT studies. The varenicline studies indicate that 90% of participants had previously attempted quitting and failed and that nearly 80% of placebo group members relapsed to smoking within two weeks.

CDC surveys show that 70% of U.S. smokers want to quit and that each year about 40% make a serious attempt of at least one day. Instead of yielding to the interests of the makers of NRT and allied cessation products, the CDC should have the courage to tell our 45.1 million current smokers the truth about how nearly all of our nation's 46.5 million ex-smokers really quit and what they need to do to join them.