SRNT surrenders to nicotine

Founded in 1994, one of the most influential scientific organizations, the stated mission of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) is to "stimulate the generation and dissemination of new knowledge concerning nicotine …"[1].

According to its members, the "SRNT is–first and foremost–a scientific society, whose role is to promote unbiased science."[2]

During its 27 year history, which aspect of nicotine science has the SRNT failed to stimulate and disseminate?

- Stop smoking via replacement nicotine weaning

- Switching from cigarettes to less risky delivery

- Nicotine dependency recovery

The Answer

The answer is c. The SRNT has strongly advocated smoking cessation via nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) since its inception, so much so that outsiders might think SRNT stands for Select Replacement Nicotine Therapy.

While answer b is new and the focus of this article, the SRNT has never championed nicotine cessation.

On July 16, 2021, we learned that the SRNT board of directors had voted to tell health providers that failed cigarette quitters should be encouraged to switch/transfer to next-generation tobacco products (heat-not-burn cigarettes, nicotine pouches, and e-cigarettes).

Entitled "Reappraising Choice in Addiction: Novel Conceptualizations and Treatments for Tobacco Use Disorder" (TUD),[3] the 7-page SRNT journal article gives the tobacco industry cause for excitement as it recommends, by name, the long-term use of 4 industry products: IQOS, Juul, On!, and Zyn.

SRNT Product Recommendations

IQOS is sold internationally by Philip Morris International (PMI) and marketed here by Altria, its U.S. counterpart.

As PMI explains it, "Thanks to sophisticated electronics, IQOS heats specially designed heated tobacco units [tobacco plugs within HeatSticks or HEETS] up to 350°C, without combustion, fire, ash, or smoke. This generates a flavorful nicotine-containing vapor, releasing the true taste of heated tobacco. The experience lasts about six minutes or 14 puffs, comparable to that of a cigarette. Since there is no burning, the levels of harmful chemicals are significantly reduced compared to cigarette smoke."

Delivering up to 40mg of nicotine salts, the 2014 Juul teen vaping epidemic resulted in Juul settling a N.C. youth targeting claim in June for $40 million, with more than 2,000 lawsuits pending.

Down to just 2 flavors (Virginia tobacco and menthol), according to Juul, "JUUL products deliver an exceptional nicotine experience designed for adult smokers looking for an alternative to traditional cigarettes. The JUUL Device is a vaporizer, also known as an electronic cigarette or e-cigarette, that has no buttons or switches, and uses a regulated temperature control."

Also in the news is Juul’s purchase of the entire May/June issue of a major medical journal for $51,000, and dedicating the issue to pro-vaping studies funded by Juul.

The SRNT’s Juul use recommendation hinges on whether Juul has succeeded in convincing the FDA that the sale of Juul e-cigarettes is "appropriate for the protection of public health." A ruling is expected by September 9.

On! nicotine pouches are sold online. Pouches contain 1.5 to 8 mg of tobacco-derived nicotine that’s crystallized into nicotine salts. On! is marketed by Helix Innovations LLC, a subsidiary of Altria, the parent of Philip Morris USA. Altria also owns 35% of Juul.

Ironically, while the On! website displays a prominent warning that nicotine is addictive, visitors are told to "enjoy" the pouches, that they produce "satisfaction," can be used anywhere [classrooms?], are designed to produce "maximum flavor," and come in 7 flavors: cinnamon, berry, coffee, citrus, mint, wintergreen, and original.

Zyn is also a nicotine salt pouch. According to Zyn’s maker, Swedish Match, a Stockholm-based tobacco company, "Every flavor of ZYN comes in two levels of satisfaction: 3 mg for fresh nicotine satisfaction and 6 mg for even more nicotine enjoyment."

There is substantial concern that next-generation nicotine products are adolescent addiction time bombs in waiting.[4] [5]

SRNT Switching Recommendation Premature?

True "harm reduction" is a no-brainer.

The issue isn’t the availability and use of less toxic forms of nicotine delivery, at least where informed consent includes warning that long-term use risks may not be known for decades.

It’s the logic and intellectual integrity of TUD treatment recommendations by a pharma-funded society that’s championed pharma stop smoking products since its founding, while intentionally ignoring science, research, education, and support associated with the method generating more successful quitters than all others combined.

The SRNT "choice" paper concludes that "For those who cannot wean from nicotine entirely, switching to less risky modes of delivery might be a secondary goal…"[3]

Understandably frustrated by the 40 million remaining combustible tobacco product users,[6] the SRNT switching recommendation is a natural progression after 40 years of generating and disseminating fatally flawed nicotine weaning science.

Replacement nicotine’s most vocal advocate, SRNT members helped convince the world that nicotine is "medicine" and its use "therapy." Ironically, today the tobacco industry uses NRT to help sell the safety of new unsafe nicotine products.

Readers of PMI’s "Product Addictiveness" page are told, "In fact, nicotine is a key ingredient in nicotine replacement therapies designed to help smokers quit smoking."

But what if the SRNT was wrong about NRT helping smokers quit? What if over-the-counter (OTC) NRT—how nearly all replacement nicotine is sold and used—actually undercuts successful quitting?

If so, should the SRNT be trusted in telling failed NRT quitters that their best-remaining hope is purchase and use of IQOS, Juul, On! or Zyn?

The NRT Ineffectiveness Science-Base

Unlike the real-world quitting pool, randomized clinical trials studied a unique population of smokers seeking free "medicine" or NRT, quitters willing to delay their attempt until told to quit.

Why is that important? Because it's impossible to randomize unplanned quitting. Because population-level studies evidence that planned attempts are up to 240% less successful than abrupt or spontaneous quitting,[7] [8] [9] and OTC NRT is generally less effective than quitting without it.

A 2002 JAMA study found that "Since becoming available over the counter, NRT appears no longer effective in increasing long-term successful cessation…"[10] But the courage to speak truth to power isn’t without reputation consequences.[11] [12]

Despite the SRNT’s "choice" paper doing so, the body of evidence documenting OTC NRT’s real-world ineffectiveness conflict with "double your chances" clinical efficacy findings is now nearly impossible to ignore.

A 2014 prospective cohort study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings found that "use of NRT bought over the counter was associated with a lower odds of abstinence (odds ratio, 0.68; 95% CI)."[13]

More recently, a 2018 prospective study presented data indicating that cold turkey was 11 times more productive than NRT and 3.3 times as effective (see Table 7).[14]

What does it say about the foundational integrity of the SRNT’s "choice" paper in failing to mention cold turkey when a 2021 Urology study found that 115 of 151 smokers with bladder cancer attempted quitting, with most attempting cold turkey (63 of 115 or 54%), and most succeeding cold turkey (42 of 64 or 66%)?[15]

Should "choice" and new choice policy recommendations be taken seriously when the world’s most productive choice is ignored?

The SRNT’s "choice" conclusions remind me of the 2021 McDermott study which concluded that "When used daily, electronic cigarettes appear to facilitate abstinence from smoking when compared with using no help." McDermott ignores its own data showing that among the 203 responders most likely to have ended nicotine use and fully arrested their chemical dependence (168 unassisted quitters, 23 medication quitters, and 12 e-cigarette quitters who had stopped using e-cigs at follow-up), that 83 percent did so unassisted ("no-help").[16]

Even the Surgeon General’s 2020 Smoking Cessation Report reluctantly acknowledged that cold turkey generates more successful real-world quitters than all other methods combined and at rates equal or superior to NRT (see page 15).[17]

Placebo Blinding Integrity

Nearly all clinical trials were placebo-controlled. While the gold standard in most research, with smoking cessation it’s been license to steal.

Researchers recognized prior to the 1984 FDA approval of Nicorette nicotine gum that blinding quitters as to the onset or absence of withdrawal might be impossible.[18] [19]

Replacement nicotine "science" is rooted in the fiction that dangling free NRT or "medicine" as study recruiting bait doesn’t foster substantial expectations, and that experienced quitters haven’t become experts at recognizing the presence or absence of their withdrawal syndrome (a rising tide of anxieties, anger, dysphoria, concentration difficulty and sleep fragmentation within 24 hours of quitting).[20]

How bad were blinding failures? A still unknown number/percentage of clinical studies resorted to the extreme of using active placebos (provided by the pharmaceutical industry) [21] containing nicotine.

In a 1982 Nicorette approval study, "The placebo gum contained 1 mg nicotine and its biological availability was reduced by the lack of an alkaline buffer to promote absorption through the buccal mucosa." "In pretrial tests the placebo gum did produce appreciable plasma nicotine concentrations with excessive chewing (117 nmol/l (19 ng/ml) when chewed half-hourly for four hours)."[22]

In a 1996 nicotine patch study, "Patients in the P [placebo] group received a transdermal formulation with a very low content of nicotine (13% of the active form), a dose which is conventionally felt to be too low to affect outcome."[23]

A 1997 nicotine patch study claimed that "to ensure that the nicotine and placebo patches were identical in terms of color and odor, the placebo patches contained a pharmacologically negligible amount of nicotine."[24]

And in a 2002 patch study, Marion Merrell Dow provided active placebo patches that delivered 1mg of nicotine.[25]

Shockingly, researchers have almost totally ignored the recommendation that "clinical trials of NRT should uniformly test the integrity of study blinds," despite being expressly warned in 2004 that if not, the "validity of NRT clinical trial results could be questioned.[26]

As noted on page 17 of the 2008 Treatment Guideline Update, "Questions have been raised about medication placebo controls because individuals sometimes guess their actual medication condition at greater than chance levels. It is possible, therefore, that the typical randomized control trial does not control completely for placebo effects."[27]

"Sometimes"? How about both times since the 2004 warning?

In Dar 2005, the fact that 3.3 times as many placebo users were able to correctly identify their randomized assignment as declared wrong altered the study’s outcome.[28]

In Rose 2009, within one week of quitting, 4 times as many placebo patch users were able to correctly declare their assignment as declared wrong ("of 165 subjects receiving placebo patches, 27 believed they had received active patches, 112 believed they had not, and 26 were unsure").[29]

Nicotine Use Disorder Ignored

The SRNT’s "choice" paper recommendations are framed in terms of DSM-5 Tobacco Use Disorder (TUD), which the authors acknowledge "is defined and sustained by addiction to nicotine."

Problematic is the fact that more than 200 quitting product clinical trials were about a single method of nicotine delivery, smoking it.

While most studies assessed smoking by testing participant breath for expired carbon monoxide, body fluids (saliva, blood or urine) were rarely sampled to determine if participants had successfully arrested their dependence upon nicotine.

Why care? A 2003 study combined and averaged all seven U.S. OTC patch and gum studies. It found that only 7% of OTC study participants were still not smoking at six months.[30] The same year, the same primary authors published a second study which found that as many as 7% of successful nicotine gum quitters were still hooked on the gum at six months.[31]

A 2013 Gallup Poll asked successful ex-smokers the open-ended question, "What strategies or methods for quitting smoking were most effective for you?" After nearly 3 decades of heavy Nicorette marketing, only 1 percent credited nicotine gum.[32]

Question. What percent of the 1% were addicted to their answer? Which method was mentioned by most quitters? Hint: it’s the same method the SRNT’s failed quitter paper fails to mention.

Comparing Users to Non-Users

Another "science" concern is the fundamental fairness and integrity of comparing the accomplishment of an addict deprived of nicotine to one whose dopamine pathways continued to be chemically stimulated by nicotinic receptor agonists or partial agonists for weeks, months or indefinitely.

Competing against placebo, the first nicotine lozenge study (2002) permitted lozenge use for up to 26 weeks while the study’s abstract declared victory at 12 weeks.[33]

In a Chantix versus nicotine patch study, after 12 weeks of varenicline or 10 weeks of nicotine patch use, "NRT during the 9 months of follow-up did not disqualify a subject."[34]

Allowing nicotine users to participate and demoralize non-users in the same quitting program, is it possible that NRT contributed to compromising the effectiveness of local smoking cessation programs worldwide?[35]

If a study's objective was to monitor, evaluate and compare successful nicotine dependency recovery from TUD, wouldn't the logical starting point for comparison be full and complete nicotine cessation? Among those engaged in gradual weaning or NRT use, wouldn't "quitting day" be the day weaning or NRT use ends?

In the history of the world, a TUD recovery study comparing apples to apples has yet to be conducted.

Timing & Objective of Study Counseling

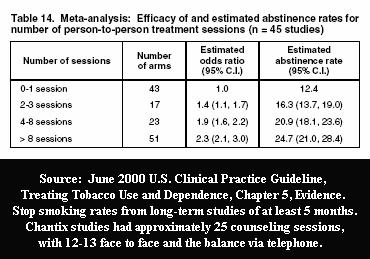

Researchers are well aware that counseling and support have their own independent efficacy.

Researchers are well aware that counseling and support have their own independent efficacy.

A 2018 propensity score analysis of 12 potential national survey confounders (including nicotine dependence, previous quit history, and cessation aid use) concluded that "the lack of effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids in increasing long-term cessation in population samples is not an artifact caused by confounded analyses. A possible explanation is that counseling and support interventions provided in efficacy trials are rarely delivered in the general population."[36]

Ask yourself, what would be your primary objective when laying out the content and timing of NRT clinical trial counseling sessions, successful transfer to the nicotine replacement product being evaluated, or educating the placebo group as to the keys to successful abrupt nicotine cessation?

The body becomes 100% nicotine-free, the brain is forced to begin restoring natural sensitivities, and withdrawal peaks in intensity within 3 days of abruptly ending nicotine use.

With cold turkey, when considering the optimum timing and intensity of counseling and support, the greatest need is clearly within the first four days.

Coupled with withdrawal awareness and frustrated expectations, it’s a reality that explains why most of the placebo group had relapsed by the time nearly all NRT studies made their first post-cessation participant contact.

Careers, reputations, tenure, 401Ks and professional societies could have been built upon Alcohol Replacement Therapy (ART). The synergy of frustrated placebo groups experiencing full-blown withdrawal could have combined with the timing and intensity of gradual weaning counseling and/or support to produce newsworthy ART efficacy victories.

The ART industry could have used its economic muscle to author Guidelines declaring AA meetings non-science-based and recommending that all patients attempting cessation receive ART.

Decades of advocacy declaring ART science-based could have influenced Google’s army of website "quality raters," thus diminishing search engine reputations and standing of websites questioning ART or advocating abrupt cessation.

The problem is, all the manipulation in the world doesn't alter the smoker’s natural quitting instincts.[37]

Neglected Research

Since the April 1996 Clinical Practice Guideline, the SRNT and its members have been instrumental in assisting the pharmaceutical industry in the "scientification" of smoking cessation via "medicinization."

Totally omitted from the "choice" paper is any mention of how the vast majority of nicotine-dependent humans successfully arrest their dependency, via abrupt nicotine cessation.

Noting that up to three-quarters of smokers quit unassisted, Chapman and MacKenzie refer to it as "The global research neglect of unassisted quitting."

They note that organizations such as the SRNT treat unassisted quitting’s dominance as "irresponsible or subversive," while ignoring "the potential policy implications of studying self-quitters."[38]

Having championed the 1996, 2000 and 2008 Guidelines, which by omission declare cold turkey non-science-based, how many of the SRNT’s more than 1,200 members know the key to successful abrupt nicotine cessation?

Cold Turkey’s Key

Most stop smoking researchers can tell us the average number of quitting attempts a smoker makes before succeeding, with a 2016 study concluding "30 or more."[39] What few are able to explain is why.

Webster’s 1973 definition of cold turkey is the "abrupt complete cessation of the use of an addictive drug either voluntarily or under medical supervision."

What lesson do many quitters self-discover after years of failed attempts? It’s that one equals all, that one cigarette is too many, while thousands are not enough; to never take another puff.

What would be the consequences for first time quitters if the SRNT chose to "stimulate and disseminate" that lesson?

What do all successful cold turkey quitters have in common? They eliminated nicotine from their bloodstream.

While not nearly as critical to gradual stepped-down weaning—where each NRT use is effectively a lapse—the 1990 Brandon lapse/relapse study found that "The high rate of return to regular smoking (88%) once a cigarette is tasted suggests that the distinction between an initial lapse and full relapse may be unnecessary."[40] Also see Garvey 1992, where 95 percent of lapses led to relapse.[41]

And let's not forget that some involved in lapse/relapse studies were likely chippers, who are somehow immune to chemical dependence.

The question begging research is, what are the annual net relapse consequences of nearly all stop smoking websites—sites dedicated to NRT—effectively teaching that "slips" are normal, expected and easily overcome?

We tell smokers the truth about nearly all lung cancers being caused by smoking but not about nearly all lapses ending in relapse. Why?

Financial Conflicts

It’s gotten easier to appreciate the intensity of biases generated when voters are almost exclusively subjected to far left or right media.

Still, many researchers fail to grasp how studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies are up to 4 times more likely to generate findings favoring the sponsor.[42]

SRNT group-think reflects a quarter of a century of the Society accepting pharmaceutical industry funding and memberships, while paying fealty to the makers of the very stop smoking products the Society has anointed as being science-based (2019).

In 2013, Professor Michael Siegal attacked the SRNT for allowing GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson to sponsor its annual meeting, while the SRNT’s convention webpage and program flyer failed to disclose it.

Calling the meeting a "scientific farce," pharma sponsorship creates "an unavoidable bias that precludes a truly objective consideration of any scientific issue that may have significant implications for the profitability of smoking cessation drugs…" Siegal wrote.

Many of the SRNT’s most influential members openly serve as paid pharmaceutical or tobacco industry consultants, advocates or speakers.[43] [44]

Reflect on the biases fostered after decades of referring to nicotine as "medicine" and its use "therapy." How could members not see IQOS, Juul, on!, and Zyn as good and wonderful?

Why are scores of population-level NRT ineffectiveness findings totally ignored by pharma-paid researchers?

In fairness, biting the hand that feeds you isn’t just about lost income. It could cost research funding opportunities, with loss of standing among peers.

But before that, you'd have to convince them that they'd traveled the wrong path for years. As with altering deeply engrained political biases, good luck with that.

SRNT at War With Itself

"Cessation," "medicine," "tobacco industry," "harm reduction," failure to agree upon the enemy is eroding the SRNT's cohesion and reputation.

There was a time when all cessation involved ending nicotine use, when nicotine was a toxin and natural insecticide, when it was trapped within tobacco, and when tobacco "science" tried to convince us that cigarette filters and low tar cigarettes were significant harm reduction measures.

No consensus as to basic definitions, how could the SRNT and its board of directors not be confused?

SRNT membership policy allows pharmaceutical and e-cigarette industry employees to become voting members while excluding tobacco industry employees. The workaround is that tobacco companies are free to hire a consulting company, and the consultant's employees may join.

So, how did four tobacco industry products get featured in an SRNT TUD treatment recommendation?

Marinated by pharma bias too deep to taste, despite denying them voting rights, years of allowing tobacco industry employees SRNT convention participation has the Society devouring itself.

A 2019 SRNT member survey found that 71% of respondents were "concerned" about tobacco industry participation in the SRNT Annual Meeting, with 43% favoring the total exclusion of industry employees from presenting at the convention, and 41% favoring an attendance ban.

Similarly, 65% of responding members were "concerned" about the presence and participation of the e-cigarette industry at the SRNT annual meeting.

One of the SRNT’s three 1994 founders, Dr. John Hughes, a physician and University of Vermont professor of psychiatry and psychological science, became its second president in 1995.

In 1996 Hughes wrote, "I think the pendulum has swung too far toward pharmacological treatments and would like to see some innovative behavior therapy research. I would even like to see a return to adequate testing of some basic questions—e.g., is abrupt or gradual cessation better …?"

Professor Hughes’ 2018 CV indicates that he has served as a consultant to Ciba-Geigy, Glaxo Wellcome, McNeil Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, SmithKline Beecham, and GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare.

Since 2017, Hughes has also served as a deputy editor of the SRNT’s journal, Nicotine & Tobacco Research. His December 2019 journal conflicts disclosure declares that he has accepted payment from and "Consults with Swedish Match, Altria and Philip Morris on their efforts to develop less-risky tobacco products."

On July 7, 2021, the SRNT board of directors notified the tobacco industry that tobacco industry employees would no longer be allowed to attend the SRNT’s annual conference.

Not only has the policy change been objected to by Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco, according to MUSC Professor Michael Cummings, "John Hughes is resigning from the organization, which is sad to see, and others who I’ve heard from as well" (see 12:50).

Cummings recalls the SRNT’s old policy of allowing tobacco industry researchers to make presentations to SRNT but not allowing them to be voting members.

"I think that's actually a very reasonable compromise. By the way, I would extend that to the pharmaceutical industry as well, which has for years been major sponsors of our annual meeting at SRNT" (see 13:04) "It's the worst possible decision I can possibly think of," says Cummings, "to keep the science out" (see 14:20).

Bloomberg School of Public Health Professor Joanna Cohen reminds us that science is based on the honor system. "[T]he bottom line is that scientists do not want their journals or their scientific societies to be used in the service of an industry that continues to perpetuate the most deadly disease epidemic of our time" (see 19:32)

According to UCSF Professor Neal Benowitz, one of the authors of the SRNT’s "choice" paper, one of the reasons given for the policy change is that the presence of tobacco industry employees makes some SRNT members "uncomfortable." (see 11:30)

Addressing "comfort," Cohen shared her own personal experience. "I had a pre-conference workshop accepted at the Florence conference in 2017. We had presenters and discussants and it was a workshop, so we were going to have time for people to work at their tables and brainstorm ideas."

But two weeks prior to the conference she discovered that 23% of those registered for the workshop were tobacco company employees. "I wasn't comfortable making people sit at the same table as tobacco company employees to brainstorm solutions to the problems that the companies created."

Cohen felt that in group brainstorming sessions that employees wouldn't openly share their knowledge and ideas. "[T]he companies aren't incentivized to share this knowledge openly, and not with their competitors, and not with tobacco control professionals who are working to reduce the use of their products."(see 16:58).

But couldn’t similar arguments be made about the SRNT being married to GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer?

Frustrated Failed Quitters

Will the Society’s directors vote to listen to the 1996 Professor Hughes and seek answers to fundamental nicotine dependency recovery questions, or placate the 2021 Hughes and gift the neo-nicotine industry the legitimacy and platform needed to addict another century of humans to the planet’s most captivating chemical? Stay tuned.

As shared in my July 19 journal comment to the "choice" article, dependency’s greatest harm isn’t some use-related disease decades down the road. It’s how every waking hour of every day until then gets lived, as a slave to mandatory nicotine feedings.

The SRNT board would be wise to reflect upon the sanity of voting TUD as a treatment for TUD when the SRNT helped brainwash failed quitters into believing that nicotine—the enemy—is good, not bad.

References

1. ↩ Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, What We believe: Society Mission. https://www.srnt.org/page/Mission_and_Values. Accessed 08/15/21

2. ↩ SRNT, 2025 Strategic Review: Phase I Final Report. 2020, https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/2025_member_comment/srnt_2025_phase_i_final_repo.pdf

3. ↩ Amanda M Palmer, PhD, Benjamin A Toll, PhD, Matthew J Carpenter, PhD, Eric C Donny, PhD, Dorothy K Hatsukami, PhD, Alana M Rojewski, PhD, Tracy T Smith, PhD, Mehmet Sofuoglu, MD, PhD, Johannes Thrul, PhD, Neal L Benowitz, MD, On Behalf of the Society for Research on Nicotine & Tobacco Treatment Network, Reappraising Choice in Addiction: Novel Conceptualizations and Treatments for Tobacco Use Disorder, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2021;, ntab148, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab148

4. ↩ Li S, Braden K, Zhuang YL, Zhu SH. Adolescent Use of and Susceptibility to Heated Tobacco Products. Pediatrics. 2021 Aug;148(2):e2020049597. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-049597. PMID: 34312293.

5. ↩ Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Abroms LC, Rodnay M, Elbaz D, Khayat A, Levine H. Assessment of IQOS Marketing Strategies at Points-of-Sale in Israel at a Time of Regulatory Transition. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021 Jul 3:ntab142. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab142. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34216461.

6. ↩ Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1736–1742. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4

7. ↩ Garnett C, Shahab L, Raupach T, West R, Brown J. Understanding the Association Between Spontaneous Quit Attempts and Improved Smoking Cessation Success Rates: A Population Survey in England With 6-Month Follow-up. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020 Aug 24;22(9):1460-1467. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz115. PMID: 31300827; PMCID: PMC7443601.

8. ↩ Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, Gitchell JG, Sembower MA, West R. Unplanned quit attempts--results from a U.S. sample of smokers and ex-smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009 Jul;11(7):827-32. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp072. Epub 2009 Jun 9.

9. ↩ West R, Sohal T. "Catastrophic" pathways to smoking cessation: findings from national survey. BMJ. 2006 Feb 25;332(7539):458-60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38723.573866.AE. Epub 2006 Jan 27.

10. ↩ Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Impact of Over-the-Counter Sales on Effectiveness of Pharmaceutical Aids for Smoking Cessation. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1260–1264. doi:10.1001/jama.288.10.1260

11. ↩ Stead LF, Davis RM, Fiore MC, Hatsukami DK, Raw M, West R. Effectiveness of Over-the-Counter Nicotine Replacement Therapy. JAMA. 2002;288(24):3109. doi:10.1001/jama.288.24.3109-JLT1225-1-4.

12. ↩ Franzon M, Gustavsson G, Korberly BH. Effectiveness of Over-the-Counter Nicotine Replacement Therapy. JAMA. 2002;288(24):3108. doi:10.1001/jama.288.24.3108

13. ↩ Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Prospective cohort study of the effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments used in the "real world". Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Oct;89(10):1360-7. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.004. PMID: 25282429; PMCID: PMC4194355.

14. ↩ Weaver SR, Huang J, Pechacek TF, Heath JW, Ashley DL, Eriksen MP. Are electronic nicotine delivery systems helping cigarette smokers quit? Evidence from a prospective cohort study of U.S. adult smokers, 2015-2016. PLoS One. 2018 Jul 9;13(7):e0198047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198047. PMID: 29985948; PMCID: PMC6037369.

15. ↩ Bassett JC, Matulewicz RS, Kwan L, McCarthy WJ, Gore JL, Saigal CS. Prevalence and correlates of successful smoking cessation in bladder cancer survivors. Urology. 2021 Jan 13:S0090-4295(21)00047-9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.12.033. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33450283.

16. ↩ McDermott MS, East KA, Brose LS, McNeill A, Hitchman SC, Partos TR. The effectiveness of using e-cigarettes for quitting smoking compared to other cessation methods among adults in the United Kingdom. Addiction. 2021 Mar 9. doi: 10.1111/add.15474. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33751671.

17. ↩ USDHHS. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2020.

18. ↩ DHHS PHS Food and Drug Administration, Drug Abuse Advisory Committee, Wednesday, June 22, 1983. Available from: https://whyquit.com/NRT/FDADrugAbuseAdvisoryCommittee062383.pdf

19. ↩ Polito JR, FDA knew stop smoking product clinical trials not science-based. Feb 2, 2019 WhyQuit

20. ↩ Polito JR. Smoking cessation trials. CMAJ. 2008;179(10):1037-138. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1080096

21. ↩ Greene NM, Taylor EM, Gage SH, Munafò MR. Industry funding and placebo quit rate in clinical trials of nicotine replacement therapy: a commentary on Etter et al. (2007). Addiction. 2010 Dec;105(12):2217-8; author reply 2219. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03155.x. PMID: 21054610.

22. ↩ Jarvis M J, Raw M, Russell M A, Feyerabend C. Randomised controlled trial of nicotine chewing-gum. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982; 285 :537 doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6341.537

23. ↩ Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM. Transdermal nicotine plus support in patients attending hospital with smoking-related diseases: a placebo-controlled study. Respir Med. 1996 Jan;90(1):47-51. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(96)90244-9. PMID: 8857326.

24. ↩ Sønderskov J, Olsen J, Sabroe S, Meillier L, Overvad K. Nicotine patches in smoking cessation: a randomized trial among over-the-counter customers in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol. 1997 Feb 15;145(4):309-18. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009107. PMID: 9054234.

25. ↩ Ahluwalia JS, Richter K, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia HK, Choi WS, Schmelzle KH, Resnicow K. African American smokers interested and eligible for a smoking cessation clinical trial: predictors of not returning for randomization. Ann Epidemiol. 2002 Apr;12(3):206-12. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00305-2. PMID: 11897179.

26. ↩ Mooney M, White T, Hatsukami D. The blind spot in the nicotine replacement therapy literature: assessment of the double-blind in clinical trials. Addict Behav. 2004 Jun;29(4):673-84. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.010. PMID: 15135549.

27. ↩ Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008 May. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/

28. ↩ Dar R, Stronguin F, Etter JF. Assigned versus perceived placebo effects in nicotine replacement therapy for smoking reduction in Swiss smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 Apr;73(2):350-3. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.350. PMID: 15796644.

29. ↩ Jed E. Rose, Joseph E. Herskovic, Frederique M. Behm, Eric C. Westman, Precessation treatment with nicotine patch significantly increases abstinence rates relative to conventional treatment, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 11, Issue 9, September 2009, Pages 1067–1075, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp103

30. ↩ Hughes, JR, Shiffman, S, et al., A meta-analysis of the efficacy of over-the-counter nicotine replacement, Tobacco Control, March 2003, Volume 12, Pages 21-27. 21-27.

31. ↩ Shiffman S, et al, Persistent use of nicotine replacement therapy: an analysis of actual purchase patterns in a population based sample, Tobacco Control, September 2003, Volume 12(3), Pages 310-316.

32. ↩ Gallup Poll, Most U.S. Smokers Want to Quit, Have Tried Multiple Times, July 31, 2013

33. ↩ Shiffman S, Dresler CM, Hajek P, Gilburt SJ, Targett DA, Strahs KR. Efficacy of a nicotine lozenge for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Jun 10;162(11):1267-76. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1267. PMID: 12038945.

34. ↩ Aubin HJ, Bobak A, Britton JR, Oncken C, Billing CB Jr, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR. Varenicline versus transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation: results from a randomised open-label trial. Thorax. 2008 Aug;63(8):717-24. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.090647. Epub 2008 Feb 8. PMID: 18263663; PMCID: PMC2569194.

35. ↩ Hurt RD, Offord KP, Hepper NG, Mattson BR, Toddie DA. Long-term follow-up of persons attending a community-based smoking-cessation program. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988 Jul;63(7):681-90. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65530-x. PMID: 3386308.

36. ↩ Leas EC, Pierce JP, Benmarhnia T, White MM, Noble ML, Trinidad DR, Strong DR. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical smoking cessation aids in a nationally representative cohort of American smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018 Jun 1;110(6):581-587. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx240. PMID: 29281040; PMCID: PMC6005055.

37. ↩ Doran CM, Valenti L, Robinson M, Britt H, Mattick RP. Smoking status of Australian general practice patients and their attempts to quit. Addict Behav. 2006 May;31(5):758-66. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.054. Epub 2005 Aug 31. PMID: 16137834.

38. ↩ Chapman S, MacKenzie R. The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences. PLoS Med. 2010 Feb 9;7(2):e1000216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000216. PMID: 20161722; PMCID: PMC2817714.

39. ↩ Chaiton M, Diemert L, Cohen JE, et al. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011045. Published 2016 Jun 9. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011045

40. ↩ Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: the process of relapse. Addict Behav. 1990;15(2):105-14. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-n. PMID: 2343783.

41. ↩ Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addict Behav. 1992;17(4):367-77. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-t. Erratum in: Addict Behav 1992 Sep-Oct;17(5):513. PMID: 1502970.

42. ↩ Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326(7400):1167-1170. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167

43. ↩ SRNT, Disclosure—Society For Research On Nicotine And Tobacco 22nd Annual Meeting. 2016 https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/Conferences/2016_Annual_Meeting/2016_Disclosure_Summary.pdf Accessed 08/15/21

44. ↩ Amedco, CE/CME Learner Notification Society for Research on Nicotine & Tobacco Annual Meeting 2018 https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/conferences/2018_Annual_Meeting/SRNT_-_Learner_Notification_.pdf Accessed 08/15/21