Chantix study joins negative findings omissions club

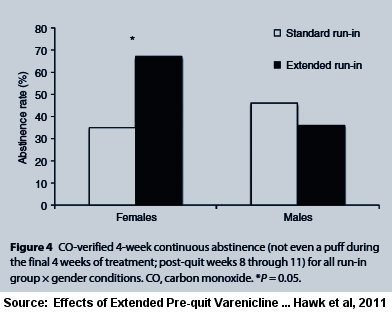

Imagine a clinical trial finding that extended use of the controversial stop smoking pill Chantix (varenicline) for three weeks longer than normal prior to the target quit smoking day benefited women but not men; that, although not statistically significant, that extended Chantix use by men actually resulted in a 22 percent worse quitting rate than standard treatment.

But that's not the problem. What's disturbing is that the study's free summary (its abstract) discussed success among women while failing to mention the results in men.

The new study, referred to here as "Hawk 2011" after its first listed co-author, was conducted at the Roswell Park Cancer Center. It's entitled, "The Effects of Extended Pre-Quit Varenicline Treatment on Smoking Behavior and Short Term Abstinence: a Randomized Clinical Trial."

The study involved comparing one group who received four weeks of pre-quitting Chantix instead of the normal one week (the "extended" group), to another group which took placebo look-a-like pills for three weeks, before receiving the normal one week of pre-quitting Chantix (the "standard"group), and then both groups continuing to take Chantix during the normal 11 week post-quitting treatment period.

The full-text copy of the Hawk 2011 study has recently become free. What if it was your job to write the Hawk 2011 study abstract? If mentioning the short-term, 12-week extended use success rate achieved by women, would it be proper to not mention the study's failure to prove worth in men?

The study's title says it's in part about "Short Term Abstinence." The abstract's only mention of abstinence states, "The rate of continuous abstinence during the final 4 weeks of treatment was higher among women in the Extended group compared to women in the Standard run-in group (67% vs. 35%). Although these data suggest that extension of varenicline treatment ... may further enhance cessation rates, confirmatory evidence is needed from phase III clinical trials."

What about men? Taken together, do these two study abstract sentences imply and leave readers with the impression that the study's data found that extension of varenicline treatment also enhanced quitting rates for men, but likely to some lesser degree than the mentioned improvement among women? If so, there was no such enhancement.

According to the $32.00 full-text version of Hawk 2011, "By contrast, there were no differences in continuous abstinence rates between the Extended (36%) and Standard (46%) groups in men (OR=0.60, 95% CI, 0.114-3.17, P=0.5)."

According to the $32.00 full-text version of Hawk 2011, "By contrast, there were no differences in continuous abstinence rates between the Extended (36%) and Standard (46%) groups in men (OR=0.60, 95% CI, 0.114-3.17, P=0.5)."

The other stated purpose of the Hawk 2011 study was to learn whether longer pre-quitting Chantix use would reduce the number of cigarettes smoked daily prior to quitting. Again, the study abstract omits the finding in men.

Here, the Hawk 2011 abstract states, "During the pre-quit run-in, the reduction in smoking rates was greater in the Extended run-in group than in the Standard run-in group (42% vs. 24%, P less than 0.01), and this effect was greater in women than in men (57% vs.26%, P =0.001)." The final abstract sentence reads in part "... these data suggest that extension of varenicline treatment reduces smoking during the pre-quit period ..."

Taken as a whole, do the above two abstract sentences suggest and imply to readers that extended pre-quitting Chantix use reduced pre-quitting smoking in men when compared to standard usage in men? If so, the abstract is misleading.

According to the full-text of the study, "Women in the Extended group showed a greater reduction in CPD [cigarettes per day] than women in the Standard group (mean difference = 4.9 CPD, P=0.003). There was no treatment effect for the men (mean difference =0.78 CPD, P=0.98)."

In fairness to the authors, neither the male abstinence rate nor the male smoking reduction rate was statistically significant. So instead of the abstract's final sentence leading readers to believe that the study's data suggested otherwise, why not simply mention male findings?

Financially Conflicted Co-authors

The Hawk 2011 study lists seven co-authors. One is Dr. Martin C Mahoney. According to the full study's conflicts of interest disclosure, Dr. Mahoney "has served" on Pfizer's Speaker's Bureau. Pfizer is the pharmaceutical company that makes and sells Chantix. The study discloses that Pfizer helped fund the study. On February 3, 2009, the National Institute of Health's clinical trials registry identified Pfizer as a study collaborator and Dr. Mahoney as its principal investigator. The full study notes that Dr. Mahoney helped design the study, co-authored the study manuscript and helped perform research.

Another named co-author and study designer was Dr. K. Michael Cummings. According to the full study's conflicts disclosure, Dr. Cummings "reports receiving consulting fees from Pfizer for work on smoking cessation."

Imagine being a glorified salesman who had served on Pfizer's speaker's bureau or a co-author collaborating with Pfizer while working beside one of its paid consultants. Could financial bias, relationship bias or research aspirations have somehow unconsciously influenced you to summarize the study's findings in manner favorable to your influences?

Biases are not created by money alone. Violations of the moral obligation for disinterestedness in science can also arise from the aim of promoting the researcher's career. To quote Matthias Adam quoting Robert K. Merton, "disinterestedness is part of the ethos of science since it serves the institutional goal of science, namely 'the extension of certified knowledge'"(Adam 2008).

Suicidal Thoughts

Table 2 in the Hawk 2011 full-text indicates that among the study's sixty Chantix users that one within the regular treatment group experienced "suicidal thoughts."

I asked Dr. Hawk whether the Table 2 suicidal thought participant was the same person discussed within the text of the study as having experienced "feelings of hostility and irritability 3 weeks after being started on varenicline."

"That was the same person," replied Dr. Hawk. "I have checked with our study's Medical Director and his recollection is that the primary concern with this person was hostility."

If writing the study abstract, would you have alerted readers that even among this rather small sampling of sixty Chantix quitters, that one experienced suicidal ideation? If writing the study's manuscript, would you have devoted a sentence or two toward bringing readers current on the number of serious adverse events in Chantix users that had so far been reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)?

According to a 2011 Chantix adverse events study, through September 2010 the FDA had received 9,575 serious case reports for Chantix, including 2,925 reported cases of suicidal/self-injurious behavior or depression. Would you have suggested, as did that study, that "The findings for varenicline, combined with other problems with its safety profile, render it unsuitable for first-line use in smoking cessation"?

In fairness to the authors, medical journals often limit the size of articles. But increasingly, journals are permitting authors to make additional documents available online, as advancing technology diminishes the cost of doing so to almost nothing.

Key Finding: Chantix Studies Not Blind

The most troubling news omitted from the Hawk 2011 abstract was that the study failed its blinding integrity assessment. To Hawk 2011's credit, it was the first Chantix study in history to admit to having tested the integrity of study blinding, and the first to publish results.

Hawk 2011's blinding failure challenges assertions that participants randomized to either Chantix or placebo in all prior Chantix clinical trials were blind as to assignment. It raises concern that all Chantix findings to date have been infected and distorted by the collision between assignment expectations and assignment awareness.

While placebo controls remain the gold standard in most research areas, smoking cessation treatments are unique in seeking to minimize a condition - withdrawal - which does not exist until its onset is commanded by researchers ("ready, set, quit"). It may be the only study area where participants randomized to placebo are actually punished with significant withdrawal anxieties and made significantly more distressed than when they arrived.

Expectations in stop smoking trials can be as thick as syrup. Researchers often dangle free quitting products in front of smokers in order to entice participation. Those taking the bait are not cold turkey quitters expecting to meet, greet and defeat their withdrawal syndrome. Instead, they're a population expecting to avoid or minimize it.

We are not told in Hawk 2011 whether study marketing alerted smokers that the study involved medication or Chantix. According to the full-text, "adult smokers were recruited through advertisements in newspapers and television and through Web posting and email."

But group expectation dynamics within cross-over studies such as Hawk 2011 differ from the normal "all or nothing" placebo-controlled quitting study. While the informed consent process surely alerted smokers to the product being tested and known risks or side-effects, it also likely mentioned that regardless of initial randomized assignment, that all participants would eventually receive a full, standard course of Chantix treatment.

Although not much of a factor here, inadequate smoking cessation study blinding can predetermine victory of defeat. Reflect on the synergy between "medicine" recruiting marketing which leaves participants drooling over the prospect of free medication, an informed consent process which teaches them the common side effects normally seen, and the fact that smokers with lengthy quitting histories have become experts at recognizing their withdrawal syndrome.

And the average smoking cessation clinical trial is loaded with expert quitters. For example, in Hawk 2011 almost 90% of participants assigned to standard Chantix treatment had made at least one prior quitting attempt (male=91%, female=88%). What we don't know is the percentage who made five or even ten prior tries.

Ask yourself, if you'd joined a trial seeking weeks or months of free NRT (nicotine replacement therapy), Zyban (bupropion) or Chantix (varenicline), how would you have reacted upon sensing that you'd been randomly assigned to a placebo look-a-like instead?

We've known since 2004 that NRT clinical trials were generally not blind as claimed (Mooney 2004). Blinding assessments made within the first week of quitting find that 3 to 4 times as many assigned to placebo correctly identify their assignment as guess wrong (Dar 2005, Rose 2009).

Frustrated and fulfilled expectations likely contribute to NRT clobbering placebo inside clinical trials (often doubling rates), yet NRT failing to prevail over cold turkey quitters in any long-term population level quitting method survey to date (Doran 2006, Australia, Hartman 2006, U.S. - see pages 35-36)

What makes the Hawk 2011 blinding assessment findings so important is that participants were asked to guess their assignment to Chantix or placebo a week prior to their target quitting date. Thus, it's difficult to contend that Chantix's worth as a quitting aid had somehow unmasked or biased guessing.

Far from being blind, 75 percent of participants receiving Chantix correctly identified their assignment a week prior to their target quitting date. For many, it wasn't a matter of guessing but actual awareness that a foreign chemical was present inside their body, bloodstream and brain.

According to Dr. Hawk, "We asked them to make a forced choice. That was followed with a 'how sure' question, but our analyses focused on the forced choice."

That awareness driven choice arose from the combination of a laundry list of known Chantix side effects (including nausea, insomnia and abnormal dreams), awareness by females of smoking fewer cigarettes per day (an average of 5 fewer in the extended group), and what the study's authors describe as "significant decreases in the rush provided by the first cigarette of the day across the pre-quit period" (varenicline with its 24 hour elimination half-life acts as an antagonist blocking nicotine from binding to a4b2 receptors).

Blinding integrity was questioned after the first extended pre-quit Chantix use study, Hajek 2011. There, it was correctly hypothesized that "failure of the blind was likely greater in the active than placebo group."

Surprisingly, even within Hawk 2011's pre-quitting placebo group, 61% correctly identified their assignment. But how? Apart from the symptoms learned during informed consent, Pfizer's Chantix television ads review a host of symptoms. How many times were participants bombarded by such ads stating that "The most common side effect is nausea. Patients also reported trouble sleeping and vivid, unusual or strange dreams"?

But how much would the placebo group's 61 percent awareness that it wasn't experiencing named Chantix symptoms have climbed a week later if, instead of researchers having reassigned them to cross-over and begin taking Chantix, researchers had commanded them to stop smoking?

Within 24 hours of quitting, what percentage would have recognized the same level of anxiety, anger, dysphoria, concentration difficulty and sleep fragmentation seen during previous failed attempts? How many would have grown frustrated at recognizing their placebo assignment, so frustrated that they would have throw in the towel and relapsed?

Upon being commanded to quit, how much higher would the extended Chantix group's 75 percent Chantix assignment belief have climbed upon discovery that their normal and expected withdrawal syndrome had significantly changed or was absent?

Do Ends Justify Means?

According to the Centers for Disease Control, there were 35.4 million daily U.S. smokers during 2010. Each year approximately 443,000 Americans smoke themselves to death, with roughly half of all current adult smokers scheduled to follow suit, each dying an average of 14 years early.

Hawk 2011 generated a rather impressive 67 percent 12-week quitting rate in extended pre-quit use women. Given smoking's horrific death toll, doesn't that justify the abstract's failure to mention the study's extended Chantix use results among men? Before getting too excited, it should be noted that Hawk 2011 created one of the most artificial quitting climates ever.

For starters, how many real-world quitters concerned about smoking's health risks make 8 visits to one of the nation's premier cancer treatment centers while quitting? How many have their vital signs taken eight times in a cancer center, are interviewed eight times about smoking and quitting, and have their breath tested eight times for expired carbon monoxide?

Hawk 2011's findings reflect 12-week quitting rates. Looking back at earlier, longer Chantix trials, what long term rate might we expect to see at one year? The 12-week Chantix rate in Gonzales 2006, one of Chantix's initial FDA drug approval studies, was 44 percent. By one year the percentage of surviving quitters had fallen by half to 22 percent.

Although not mentioned in the Hawk 2011 abstract, the study's quitters were clearly not a fair reflection of real-world quitters. The study screened 359 applicants but only 60 were chosen. Talk about cherry-picking. That's a 17 percent participation rate, just 1 in 6. By comparison, Gonzales 2006 had a 69 percent participation rate (1,483 screened, 1,025 randomized). Even so, Gonzales 2006 was then criticized for having one of the highest exclusion rates ever.

Hawk 2011 excluded anyone having a "serious medical condition" and a number of hard to treat populations including those experiencing recent depression, or having a history of panic disorder, psychosis, bipolar disorder, or recent alcohol abuse.

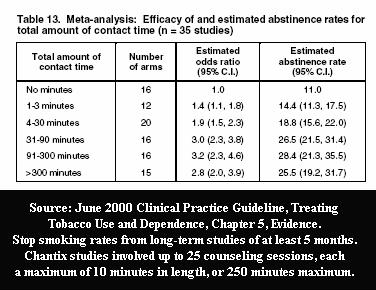

Hawk 2011 participants were paid up to $434 for attending visits and completing study measures. Also, it is generally accepted that counseling and support are highly effective and can easily double or even triple quitting rates.

Hawk 2011 participants were paid up to $434 for attending visits and completing study measures. Also, it is generally accepted that counseling and support are highly effective and can easily double or even triple quitting rates.

Aside from the study providing fifteen minutes of behavioral counseling during eight clinic visits (four before the target quit date [TQD], the TQD, and 3 post-TQD), participants were encouraged to sign up for Pfizer's online Get Quit program, which allows the option of additional regular support telephone calls and/or emails with access to Pfizer support "Coaches."

Although treated as top secret, historical cessation program participation rates suggests that the percentage of real-world Chantix users actively participating in Pfizer's Get Quit program is likely rather small. Hawk 2011 does not tell us the percentage of men and women who took advantage of Get Quit, the types of services used, the number of sessions received, or total program contact time.

Finally, unlike real world quitters, Hawk 2011 study participants conducted daily PalmPilot assessments of pre-quitting smoking patterns and smoking satisfaction. The seven week assessment period ran from a week prior to being given Chantix or placebo, through the first two weeks of quitting. Participants were alerted by an alarm, four times daily, that it was time to record cravings, withdrawal, reactivity to smoking and neutral cues.

What are the odds that Hawk 2011's 67 percent 12-week female Chantix rate would ever be reflected and mirrored in any real-world population level quitting method survey finding? Little to none.

In fact, given Chantix's failure to prevail long-term over NRT, and NRT's failure to prevail long-term over cold turkey quitting, researchers should be asking whether aggressive quitting product marketing has undermined and damaged confidence in natural cessation, stalled decline in smoking rates, and is contributing to smoker demise.

Chantix No Greater Efficacy than Nicotine Patch

So far, two clinical trials have pitted Chantix against the nicotine patch, Aubin 2008 and Tsukahara 2010. In both, Chantix failed to show statistical significance over nicotine patch quitters when assessing the percentage of users within each group who were not smoking at 24 weeks.

But you won't find that negative finding in the Aubin 2008 study abstract. There, readers are told continuous abstinence rates instead of more generally relied upon point prevalence rates, which reflect the actual number of participants who were not smoking at a given point in time (see U.S. Guideline 2008 Update, Outcome Data).

According to full-text point prevalence findings, "there were no significant differences at week 24 ... or at week 52." Aubin 2008 was funded entirely by Pfizer. The study lists eight co-authors. Four acknowledge having had financial dealings with Pfizer, while the other four were identified as current Pfizer employees.

Unlike Hawk and Aubin, the Tsukahara 2010 abstract openly announces that in comparing Chantix and nicotine patch quitting rates that "no significant difference in abstinence rates was observed between the 2 groups over weeks 9-12 and weeks 9-24." Pfizer played no role in funding Tsukahara 2010 and none of the three co-authors disclose any pharm industry financial ties.

Contrast the Aubin and Tsukahara clinical efficacy findings of "no significant differences" between patch and Chantix, with effectiveness findings from the only known U.S. Government real-world population level quit smoking method survey. It was a 2006 analysis by Ann M. Hartman (Hartman 2006) with the National Cancer Institute. Hartman examined 2003 government collected survey data from 8,200 daily smokers, who each made at least one quitting attempt of at least 24 hours during the prior year.

Hartman titled her study, "What Does U.S. National Population Survey Data Reveal About Effectiveness of Nicotine Replacement Therapy on Smoking Cessation?" She found that that at 9 months after quitting that nicotine patch quitters failed to prevail over non-medication quitters. In fact, patch quitters had a 14% nine month quitting rate versus 16% for non-medication quitters.

Laying Aubin and Tsukahara beside the government's only truly independent analysis of population level quitting methods raises serious concerns that our national cessation policy, declaring that all smokers attempting to quit should purchase and use approved quitting products, may actually be costing smokers their lives.

So what's been the government's reaction to this study findings paradox? Try to locate any government mention of Hartman 2006. Good luck. Try to locate a copy of Hartman 2006 on any government website. There is none. Freedom of Information Act requests and recent CDC communications suggest that U.S. health officials have stopped assessing real-world quitting method effectiveness; that there have been no new reports since 2006.

Failure to Feature Failure Common

What motivates honest and highly educated men and women with a PhD or medical degree to distort reality? This article should not be read to suggest that financially conflicted researchers are in any way dishonest or that it is unethical to have financial ties to the maker of the product being evaluated.

Dr. Michael Siegel, a physician-professor at Boston University School of Public Health, writes regularly regarding smoking cessation study conflicts of interest. On December 1, 2011, Dr. Siegel wrote a piece in defense of conflicted researchers. "I think that these situations involve bias, which is not related to wrongdoing, dishonesty, or lack of integrity," he wrote. "Bias is simply a perspective through which one sees, designs, conducts, interprets, and presents research."

Although not a researcher or scientist, that includes me, the author of this review. This article was influenced by my own perspective, including my own 30-year smoker histroy of quitting product and procedure failures, a history of having been paid to present cold turkey quitting programs a few years back, outrage over working with so many who run out of time and chances, and a deep rooted belief that we can and must do better.

Matthias Adam contends that objectivity is the moral obligation of every scientist. A pharmaceutical company's prime objective is profits. That, in itself, is not a conflict. Nor is ignoring society's greatest medical needs in favor of the shortest path to profits. According to Adam, problems arise when pharmaceutical companies engaged in research behave as though exempt from obligations to remain objective and impartial.

A fascinating New York Times confessions article entitled "Dr. Drug Rep" documents the unconscious consequences of accepting money from an industry without morals. It helps explain how money, corporate allegiance and stature might gradually corrupt thinking to the point of spinning study results in the "most positive way possible," while dancing around truth.

Below are three additional recent studies in which negative study findings failed to dance their way into the abstract. They involve using approved quitting products earlier, in combination or longer. While the research objective is improved quitting rates, the obvious consequence of using products earlier, more or longer is greater industry profits.

Rose 2009 compared two weeks of pre-quitting nicotine patch use to two weeks of wearing a placebo nicotine patch, before both groups received ten weeks of stepped-down treatment through the 21mg (6 weeks), 14mg (2 weeks), and 7mg (2 weeks) nicotine patches.

The results section of the Rose 2009 abstract states, "Continuous abstinence rates were approximately doubled by precessation nicotine patch treatment."

Compare that to the study's full-text which states, "While continuous abstinence rates at 10 weeks and at 6 months were enhanced by precessation nicotine patch treatment, point abstinence differed only at 1 week postquit; by 10 weeks, there was no significant difference."

When reflecting upon which quitting definition is more reliable in pre-quitting type studies - continuous or point abstinence - keep in mind that pre-quitting patch or Chantix users have longer to adjust to brain dopamine pathway stimulation via their quitting product prior to quitting day. Think about the regular group patch quitter who might fumble around for a few days before adjusting to nicotine's continuous arrival.

If they smoked a single cigarette the first day or so, they'd be counted as a failure under normal continuous abstinence definitions, yet successful under a 12, 24 or 52 week point prevalence standard. Interestingly, Rose 2009's continuous abstinence standard was measured from day #1 of post-quitting patch use, while Hawk 2011 defined continuous abstinence as the "final four weeks of treatment."

Rose 2009 was funded by Philip Morris USA, the maker of Marlboro. The study lists four co-authors, including Duke University Professor Jed E. Rose, Ph.D., the co-inventor of the nicotine patch. His conflicts disclosure states, "Dr. Rose has received royalties from sales of certain nicotine patches and is named as inventor on nicotine skin patch patents that expired in 2008."

Piper 2009 randomized participants to 1 of 6 treatment conditions: nicotine lozenge, nicotine patch, sustained-release bupropion, nicotine patch plus nicotine lozenge, bupropion plus nicotine lozenge, or placebo.

According to the results section of the study abstract, "All pharmacotherapies differed from placebo when examined without protection for multiple comparisons (odds ratios, 1.63-2.34). With such protection, only the nicotine patch plus nicotine lozenge (odds ratio, 2.34, P < .001) produced significantly higher abstinence rates at 6-month postquit than did placebo."

"Than did placebo"? Placebo isn't a real-world quitting method. Wasn't the primary purpose of the study to determine which of the six quitting methods was best? Regarding that point, according to the full-text, "It should be noted that there were no significant differences either between the 2 combination conditions or among the monotherapy conditions at any of the time points using the Bonferroni-corrected P values."

Four of the seven co-authors of Piper 2009 reported pharmaceutical industry financial conflicts of interest.

Schnoll 2010 studied extending use of the nicotine patch from the normal 8 week period to 24 weeks. Overall, the study abstract paints a rather encouraging picture of extended nicotine patch use. The problem is, if both ending patch use and measuring nicotine patch success at 24 weeks, what was actually proven? The user's well fed nicotine dependent brain has yet to attempt to live without it.

The Schnoll 2010 abstract conclusion asserts in part that, "Transdermal nicotine for 24 weeks increased biochemically confirmed ... continuous abstinence at week 24." It next hints that after ending patch use things went horribly wrong: "At week 52, extended therapy produced higher quit rates for prolonged abstinence only."

What abstract readers are not told is that according to the full-text, that among study participants assigned to wear the nicotine patch for 6 months, that only 2 of 282 had continuous abstinence from smoking for one full year.

One of the six co-authors of Schnoll 2010 had served as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, seller of the Nicoderm patch.

Why did researchers in the above examples omit what could have been headline generating findings? If willing to make the abstract free of negative findings, what other portions of the study manuscript have been painted or tainted by bias?

UK Smoking Toolkit Study

We're now seeing conflicted researchers analyze and spin population level survey findings. Dr. Robert West has developed a series of survey reviews known as the UK's Smoking Toolkit Study (STS). The most recent Toolkit paper co-authored by West is dated August 13, 2011 and entitled "Smoking and Smoking Cessation in England 2010: Findings from the Smoking Toolkit Study."

What readers of West 2011 do not see mentioned or linked to is West's financial conflicts disclosure, which was published two months earlier in another Toolkit paper, which appeared in BMC Public Health.

There, West, identified as RW, disclosed that "RW undertakes research and consultancy for the following developers and manufacturers of smoking cessation treatments; Pfizer, J & J, McNeil, GSK, Nabi, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. RW also has a share in the patent of a novel nicotine delivery device. The BMC paper, unlike West 211, also discloses that the Smoking Toolkit Study was funded in part by Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Johnson and Johnson (J & J).

The most glaring concern about West 2011 is found at the bottom of Table 1 on Page 9. There, a highly conflicted researcher presents population level quitting method survey findings as adjusted odds ratios. He does so without disclosing to readers the underlying survey counts and percentages upon which those quit smoking method odds ratios are based. It's as if West is saying, "trust me."

West's naked odds ratio assertions are baffling. While Table 1 declares that the odds of quitting via over-the-counter NRT are actually ever so slightly less than quitting totally unaided (OR=0.97), the other two Table 1 "Method used" findings are head scratching: NHS specialist support (OR=3.53**) and Medication Rx OR=1.73**).

Not only are West's asterisks not explained, there is no explanation as to why population level quitting method survey counts need to be adjusted.

West asserts beneath Table 1 that UK National Health Service (NHS) support "includes medication." Contrary to that assertion, actual one-month UK NHS Stop Smoking Services data indicates that non-medication quitting is also supported (NHS 2010-2011 Stop Smoking Services Statistics).

Also disturbing is actual 2010-11 UK NHS Stop Smoking Services data indicating 4-week stop smoking rates of 50 percent for non-medication quitters, 45 percent for NRT quitters and 59 percent for varenicline quitters (see PDF page 8 and Table 4.1 on Page 56).

Also disturbing is actual 2010-11 UK NHS Stop Smoking Services data indicating 4-week stop smoking rates of 50 percent for non-medication quitters, 45 percent for NRT quitters and 59 percent for varenicline quitters (see PDF page 8 and Table 4.1 on Page 56).

What's notable about these figures is that by the one month mark non-medication quitters are already becoming comfortable with natural dopamine pathway stimulation, while the average NRT and Chantix quitter still has another 4 to 8 weeks of treatment remaining before attempting to adjust to natural stimulation (link to all UK SSS data from 2004 through 2012).

One final point about the actual survey used by West in his UK Smoking Toolkit Survey. Frankly, it oozes pharmaceutical industry bias (click STS015). Question 514 asks which of five types of NRT have you used to try and cut down on smoking (page 2). Question 260 asks which of five types of NRT have you used in situations where you are not allowed to smoke (page 3). Question 139 asks in part if your doctor has spoken to you in the past year about using Chantix, Zyban or NRT (page 11).

But the telltale question asks about the quitting method you used during your last three quitting attempts: question 118 about your most recent attempt (page 14), question 330 about your 2nd most recent attempt (page 18), and question 336 about your third most recent attempt (page 21).

Except for omitting coding and adding a count of the 20 methods, below is how West presents his quitting method question on page 14:

"Which, if any, of the following did you try to help you stop smoking during the most recent serious quit attempt?"

PLEASE CODE ALL THAT APPLY

INTERVIEWER: PLEASE PUT "_" AROUND THE 'OTHER' ANSWERS YOU TYPE IN

- Nicotine replacement product (eg. patches/gum/inhaler) without a prescription

- Nicotine replacement product on prescription or given to you by a health professional

- Zyban (bupropion)

- Champix (varenicline)

- Attended an NHS Stop Smoking group

- Attended a non-NHS smoking support group

- Attended one or more NHS Stop Smoking one-to-one counselling/advice/support session/s

- Attended a non-NHS one-to-one counselling/advice/support session/s

- Phoned NHS Smoking Helpline

- Phoned a non- NHS Smoking Helpline

- Allen Carr Easyway session

- Allen Carr Easyway book

- Another book or booklet

- Visited www.nhs.uk/smokefree website

- Visited a website other than Smokefree

- Hypnotherapy

- Acupuncture

- Don't Know

- Nothing

- Other

Imagine being a cold turkey quitter - the most popular method of all - and never once hearing cold turkey mentioned after listening to all 20 choices. Instead, West makes them wait until choice #19 or #20 before forcing them to select "nothing" or "other."

FRIEND: "Hey, I hear you quit smoking, congratulations! What quitting method did you use?"

QUITTER: "Nothing." "Other."

And why would an admittedly financially conflicted researcher make the first four choices OTC NRT, prescription NRT, Zyban and Chantix?

Researchers are now coming to terms with the fact that medication quitting has failed to prevail over cold turkey, unassisted and non-medication quitting in nearly every real-world quitting method survey to date. But Table 1 of West 2011 may contain another valuable lesson, that abrupt cessation is nearly twice as effective as gradual withdrawal (OR=1.89**).

If correct, and again, we have no idea what the asterisks mean, wouldn't lumping ineffective gradual weaning into an unassisted or non-medication reference actually water-down and make abrupt cessation cold turkey quitting appear less effective?

It's as if West's UK Smoking Toolkit Study is an attempt to share findings suggesting that medication is superior to real world cold turkey quitting, without ever once mentioning the name of medication's leading competitor. What's needed is for West to rewrite his quitting method question and to openly share the underlying raw survey data counts for each quitting method question response alternative.

Lessons Learned

The bottom line is that smoking cessation study abstracts involving financially conflicted researchers should not be taken at face value. The problem is that unless we read the study's conflicts disclosure within the full-text, that we won't know if there were financial ties to the seller of the product being evaluated.

Even if we do read the disclosure, we have no way of knowing how much the researcher was paid by the pharmaceutical company, the date of payment or if the reason for payment was related to the product being studied.

On December 1, 2011, Dr. Siegel posed the ultimate question, should researchers with significant financial ties to the maker of the product being tested, be allowed to be involved in clinical trials of that product upon humans?

Readers of smoking cessation studies should always remain mindful that placebo is not a real quitting method, that placebo-controlled trials were not blind as claimed, and that efficacy findings achieved after excluding a substantial percentage of applicants, and then hand-feeding the survivors a rich diet of behavioral counseling and support, bear no resemblance to results achieved in real-world populations, under real-world conditions.

It's shocking that thousands of Chantix and Champix users worldwide have reported serious injury or harm yet no researcher on earth can look them in the eye and tell them Chantix's 24-week efficacy or effectiveness when used without counseling, support or Pfizer's Get Quit program. That stand-alone use study, the manner in which most quitter's are using Chantix, has yet to be conducted. Why?

Although nearly all cessation researchers admit that more smokers quit smoking cold turkey than by all other quitting methods combined, try to locate any quit smoking website telling smokers the truth about how most successful ex-smokers succeeded. Why?

Imagine researchers professing concern about America's leading cause of preventable death and then totally ignoring study of how most quitters succeed.

What's needed are impartial minds willing to explore how best to teach the key to successful abrupt nicotine cessation, mastery of the Law of Addiction, the lesson that lapse nearly always equals relapse.

But so long as government health officials continue to act and behave like financially conflicted researchers, in hiding population level findings such as Hartman 2006, while enticing smoker relapse by falsely suggesting that lapse is easily and normally overcome, it will not and cannot happen.