As Addictive as Heroin?

How many heroin addicts do you know who smoke crack every waking hour of every day? Zero!

On May 17, 1988, the U.S. Surgeon General warned that nicotine is as addictive as heroin and cocaine.[1]

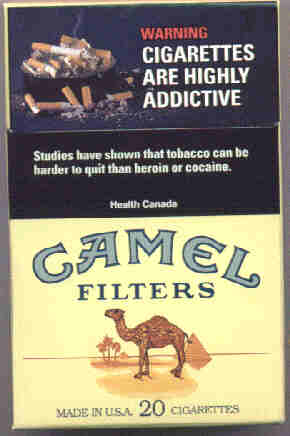

In 2000, Canada's cigarette pack addiction warning label read: "WARNING - CIGARETTES ARE HIGHLY ADDICTIVE - Studies have shown that tobacco can be harder to quit than heroin or cocaine."

But how on earth can nicotine possibly be as addictive as heroin? It's a legal product, sold in the presence of children, near candies, sodas, pastries, and chips at the neighborhood convenience store, drug store, supermarket, and gas station.

Heroin addicts describe their dopamine pathway wanting satisfaction sensation as being followed by a warm and relaxing numbness. Racing energy, excitement, and hyperfocus engulf the methamphetamine or speed addict's wanting satisfaction. Satisfaction of the alcoholic's wanting is followed by the gradual depression of their central nervous system. And euphoria (intense pleasure) is the primary sensation felt when the cocaine addict satisfies wanting.

The common link between drugs of addiction is their ability to stimulate and captivate brain dopamine pathways.

Should the fact that nicotine's dopamine pathway stimulation is accompanied by alert central nervous system stimulation blind us as to what's happened, and who we've become?

Nicotine is legal, openly marketed, taxed and everywhere. Its acceptance and availability openly invites denial of a super critical recovery truth, that we had become "real" drug addicts in every sense.

Definitions of nicotine dependency vary greatly. One of the most widely accepted is the American Psychiatric Association's as published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM IV).[2] Under DSM IV, a person is dependent upon nicotine if at least 3 of the following 7 criteria are met:

- Difficulty controlling nicotine use or unable to stop using it.

- Using nicotine more often than intended.

- Spending significant time using nicotine (note: a pack-a-day smoker spending 5 minutes per cigarette devotes 1.5 hours per day, 10.5 hours per week or 13.6 forty-hour work weeks per year to smoking nicotine).

- Avoiding activities because they might interfere with nicotine use or cutting activities short so as to enable replenishment.

- Nicotine use despite knowledge of the harms tobacco is inflicting upon your body.

- Withdrawal when attempting to end nicotine use.

- Tolerance: over the years gradually needing more nicotine in order to achieve the same desired effect.

A 2008 study found that 98% of chronic smokers have difficulty controlling use.[3] Although often criticized, the problem with DSM nicotine dependency standards is not its seven factors. It's getting those hooked upon nicotine to be honest and accurate in describing its impact upon their life.

It isn't unusual for the enslaved and rationalizing mind to see leaving those we love in order to go smoke nicotine as punctuating life, not interrupting it. And the captive mind can invent a host of excuses for avoidance of activities lasting longer than a couple of hours. It can explain how the ashtray sitting before them became filled and their cigarette pack empty without realizing it was happening.

In February 2008, I finished presenting 63 nicotine cessation seminars in 28 South Carolina prisons that had recently banned all tobacco. Imagine paying $8 for a hand-rolled cigarette. Imagine it being filled with tobacco from roadside cigarette butts, tobacco now wrapped in paper torn from a prison Bible.

Eight dollars per cigarette was pretty much the norm in medium and maximum-security prisons. The price dropped to about $2 in less secure pre-release facilities. Imagine not having $8. I heard horrific stories about the lengths to which inmates would go for a fix.

Two inmates housed in a smoke-free prison near Johnson City, Tennessee ended a six-hour standoff in February 2007 when they traded their hostage, a correctional officer, for cigarettes. According to a prison official, "They got them some cigarettes, they smoked them and went back to their cell and locked themselves back in."

I stood before thousands of inmates whose chemical addictions to illegal drugs landed them behind bars. During each program I couldn't help but comment on the irony that those caught using illegal drugs ended up in prison, while we nicotine addicts openly and legally purchase our drug at neighborhood stores.

According to the CDC, during 2011 tobacco killed 11 times more Americans than all illegal drugs combined (443,690 versus 40,239).

As discussed in the intro, Joel Spitzer may well be the world's most insightful nicotine cessation educator. My mentor since January 2000, he tells the story of how during a 2001 two-week stop smoking clinic, a participant related that he was briefly tempted to smoke after finding a single cigarette and lighter setting atop a urinal in a men's public bathroom.

What made it so tempting was that the cigarette was his brand. He thought to himself how easy it would have been to smoke it. Joel then asked the man, "When was the last time you ever saw anything else atop a urinal in a men's room that you felt tempted to put in your mouth?" At that, the man smiled and said, "Point well taken."

Over the years, ex-users have shared stories of leaving hospital rooms where their loved one lay dying of lung cancer so they could smoke, of smoking while pregnant, of accidentally lighting their car, clothing, hair or dog on fire, of smoking while battling pneumonia, and of sneaking from their hospital room into the staircase to light-up while dragging along the stand holding their intravenous medication bag.

Another story shared by Joel relates how one clinic participant had long kept secret how his still-smoldering cigarette butt on the floor had lit the bride's wedding dress on fire.

We each have our own dependency secrets. As a submarine sailor, I went to sea on a 72-day underwater deployment in 1976 thinking that stopping would be a breeze if I didn't bring any cigarettes or money along. I was horribly, horribly wrong.

I spent two solid months begging, bumming and digging through ashtray after ashtray in search of long butts.

Even worse was losing both of my dogs to cancer. One of them, Billy, died at age five of lymphoma. It wasn't until after breaking free that I read studies suggesting that smoke from my cigarettes may have contributed to their deaths.[4] If so, all this recovered addict can do now is to keep them alive in his heart while begging forgiveness.

Again, the primary difference between the illegal drug addict and us is that our chemical is legal and our dopamine wanting relief sensation accompanied by alertness.

Yes, there are social smokers called "chippers." And yes, their genetics may allow them to use yet always retain the ability to simply turn and walk away.[5] But, I'm clearly not one of them. And odds are, neither are you, as you wouldn't be reading a book about how to arrest your dependency.

I often think about the alcoholic's plight, in having to watch 90% of drinkers do something the 10% who are alcoholics cannot themselves do, control their alcohol intake. We've got it much easier.

The dependency figures for nicotine are almost the exact opposite of alcohol's. Roughly 90% of daily adult smokers are chemically dependent under DSM-III[6] standards, while 87% of students smoking at least 1 cigarette daily are already dependent under DSM-IV standards.[7]

References

- 1. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction: A Report of the Surgeon General, May 17, 1988.

- 2. American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Washington, D.C. 1994.

- 3. Hendricks, P. et al, Evaluating the validities of different DSM-IV-based conceptual constructs of tobacco dependence, Addiction, July 2008, Volume 103, Pages 1215-1223.

- 4. Roza MR, et al, The dog as a passive smoker: effects of exposure to environmental cigarette smoke on domestic dogs, Nicotine and Tobacco Research, November 2007, Volume 9(11), Pages 1171-1176; also see, Bertone ER, Environmental tobacco smoke and risk of malignant lymphoma in pet cats, American Journal of Epidemiology, 2003, Volume 156 (3), Pages 268-273; also Brazell RS et al, Plasma nicotine and cotinine in tobacco smoke exposed beagle dogs, Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 1984, Volume 73, Pages 152-158, also Bertone-Johnson ER et al, Environmental tobacco smoke and canine urinary cotinine level, Environmental Research, March 2008, Volume 106(3), Pages 361-364.

- 5. Kendler KS, et al, A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence, Psychological Medicine, March 1999, Volume 29(2), Pages 299-308.

- 6. Hughes, JR, et al, Prevalence of tobacco dependence and withdrawal, American Journal of Psychiatry, February 1987, Volume 144(2), Pages 205-208.

- 7. Kandel D, et al, On the Measurement of Nicotine Dependence in Adolescence: Comparisons of the mFTQ and a DSM-IV Based Scale, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, June 2005, Volume 30(4), Pages 319-332.