Forgotten Breathing & Endurance

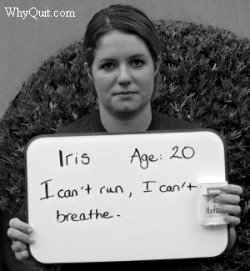

If a smoker, try to recall what it was like to run like the wind, to engage in an extended period of brisk physical activity without getting seriously winded?

Smokers not only suffer from nicotine addiction but the ravaging effects of thousands of inhaled chemicals upon their lungs and respiratory system.

What was it like to run like the wind, to engage in an extended period of brisk physical activity without becoming seriously winded?

What was it like to climb flight after flight of stairs, to play full-court basketball, or to chase a child or the family pet without ending up gasping for air?

Every now and then I meet a current smoker who proudly boasts that they enjoy running. What they don't seem to appreciate is the tremendous strain they subject their heart and body to when doing so. It's a matter of vigorously working muscles obtaining enough oxygen.

Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless toxic gas produced when any carbon-based material is burned, including tobacco. When smoking, the amount of carbon monoxide entering the bloodstream varies greatly, up to 25mg per cigarette. Variability can be related to the particular brand being smoked, how intensely the smoker smokes, or whether filter ventilation holes are covered by their lips.

Without oxygen, the body's cells suffocate and die. The primary function of our lungs is to allow the entry of life-giving oxygen from the atmosphere into our bloodstream, and to then transfer carbon dioxide from our bloodstream back out into the atmosphere.

This exchange of gases takes place within an estimated 480 million thinly walled air sacs called alveoli.[1] But sucking large quantities of carbon monoxide into our lungs changes the playing field.

Hemoglobin is a protein in red blood cells that transports a new supply of oxygen from the alveoli (air sacs) in our lungs to more than 50 trillion living cells throughout the body. One hemoglobin molecule can transport up to 4 oxygen molecules.

The problem is, when smoking, if both an oxygen molecule and a carbon monoxide molecule arrive at an air sac at the same time, the carbon monoxide molecule always wins and the oxygen molecule is always left behind.

The chemical attraction between carbon monoxide and hemoglobin is 200-250 times greater than with oxygen.[2] What's worse, once attached to hemoglobin, carbon monoxide's long chemical bloodstream half-life of 2 to 6.5 hours[3] prevents red blood cells from transporting oxygen.

Think about that last puff. One-half of the carbon monoxide it contained will still be circulating inside your bloodstream roughly four hours later. Is it any wonder that our heart and body rebelled when we attempted vigorous exercise, even hours after smoking?

We don't just deprive our heart and muscles of oxygen. We daily paint our lungs with the 4,000 chemicals that the tobacco industry collectively refers to as tar. It's too little oxygen and too much gunk.

While comforting to think that most of the toxins in the smoke that we sucked into our lungs were exhaled, it just isn't so. Ninety-seven percent of NNN (possibly the most potent lung cancer-causing chemical of all) is not exhaled but remains inside.

It's the same absorption rate as nicotine. Ninety-seven percent of inhaled nicotine isn't exhaled.[4] Imagine traveling through life with lungs so marinated and caked in toxic tars that it appreciably diminishes lung function.

What would it be like to allow nearly destroyed bronchial tube sweeper brooms, our cilia, to re-grow and begin the process of sweeping gunk from air passages? Imagine allowing all still functioning air sacs time to clean and heal.

What would it be like to experience a substantial increase in overall lung function? Imagine gifting yourself the ability to build cardiovascular endurance again, to have nearly all hemoglobin transporting life-giving oxygen.

References

- 1. Ochs M et al, The number of alveoli in the human lung, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, January 1, 2004, Volume 169(1), Pages 120-124.

- 2. Meredith T et al, Carbon monoxide poisoning, British Medical Journal, January 1988, Volume 296, Pages 77-79.

- 3. World Health Organization. Environmental Health Criteria 213 - Carbon Monoxide (Second Edition). WHO, Geneva, 1999; ISBN 92 4 157213 2 (NLM classification: QV 662). ISSN 0250-863X.

- 4. Feng S, A new method for estimating the retention of selected smoke constituents in the respiratory tract of smokers during cigarette smoking, Inhalation Toxicology, February 2007, Volume 19(2), Pages 169-179.