What is classical conditioning?

As it relates to nicotine, classical or Pavlovian conditioning is conditioning in which, through repetition, a person, place, thing, activity, time or emotion (a conditioned stimulus or CS) becomes subconsciously paired with using nicotine (an unconditioned stimulus or US). Thereafter, encountering the conditioned stimulus alone becomes sufficient to trigger wanting, an urge or a crave (a conditioned response or CR). [1]

How does classical conditioning relate to operant conditioning, which we just reviewed?

With operant learning, most of us eventually became consciously aware that use operates to reinforce using again, or that we're punished for not using soon enough. Not so with classical conditioning. Use-cue pairings happen subconsciously and are activated automatically upon encountering a previously conditioned stimulus.

While operant conditioning is tied to dependency onset and our basic nicotine replenishment cycle, classical conditioning isn't about the consequences of use. It's about a conditioned stimulus triggering wanting and use, even if not yet time for more.

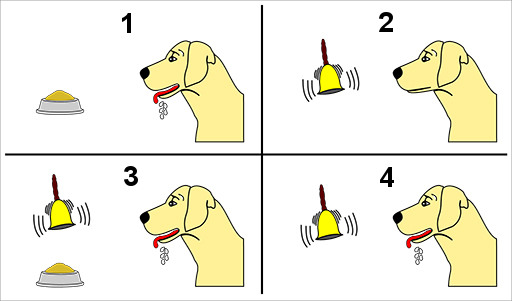

In classical conditioning, like Pavlov's dogs, which he conditioned to expect food (US) and begin salivating (CR) upon the ringing of a bell (CS), we each conditioned our subconscious to expect (CR) arrival of a new supply of nicotine (US) in specific situations (CS).

For example, your mind can be trained to want nicotine upon simply seeing a picture of a green triangle. A 2012 classical conditioning study did just that. It conditioned smokers to associate smoking (US) with an object that had previously been entirely neutral (CS).[2]

The conditioning was created by 80 times pairing a picture of a green triangle (CS) with a smoking-related picture of people holding or smoking cigarettes (US). Each pairing was shown to smokers for less than half a second (400 milliseconds). Although less than a second, the subconscious mind was watching and learning.

Not only did smokers report increased cravings (CR) upon being shown the green triangle alone without the smoking-related image, brain responses recorded by EEG (electroencephalograph) supported their claims.

Researchers have successfully used sight, smell, and hearing to establish new conditioned use cues in smokers. Encountering the new cue will trigger use expectations and an urge to smoke, with an increase in pulse rate.[3]

Interestingly, researchers find it easier to establish new cues among light smokers, who obviously have fewer existing cues than heavy smokers.

Urges & Cravings

If crave episodes feel real and physical in nature there's good reason. Although nicotine-feeding cues are psychological in origin, they trigger physiological responses within the body.

Not only do the stimulant effects of using nicotine increase pupil size, researchers also found that encountering a visual nicotine use-cue will increase pupil size, an autonomic response.[4]

Using brain scans, researchers discovered increased blood flow during cue-induced cravings in brain regions associated with "aaah" wanting relief or anxiety (the ventral striatum, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, medial thalamus and left insula).[5]

They also discovered that the amount of brain blood flow (perfusion) was tied to the intensity of the cue-induced cigarette cravings in brain regions known to control attention, motivation, and expectancy (the prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate).[6]

Years of subconscious conditioning had us reaching for a nicotine fix and engaging in replenishment without our conscious mind recognizing that we had encountered a use-cue (conditioned stimulus), and often without noticing that replenishment was underway.

Study the next smoker you see. As if on autopilot, it is very likely that the drags you'll watch being inhaled will be taken while their unconscious mind is in full control.

I can't begin to count the number of times I looked down and was surprised to see the ashtray full and the pack empty.

While nicotine's two-hour elimination half-life seems more closely tied to operant conditioning, classical conditioning is tethered to historic use patterns and circumstances. Still, interwoven within nicotine's operant need-feed cycle, it's hard to say which form of conditioning contributes most toward gradually increasing nicotine "tolerance."

What are the consequences of using when full? Might it cause the brain to gradually need a bit more in order to feel nicotine-normal? Or does it simply delay arrival of operant reinforcement?

Although unaware, we each established daily replenishment patterns which trained and alerted our subconscious as to circumstances to expect more.

References:

2. Littel M and Franken IH, Electrophysiological correlates of associative learning in smokers: a higher-order conditioning experiment, BMC Neuroscience, January 11, 2012, 13:8.

3. Lazev AB, et al, Classical conditions of environmental cues to cigarette smoking, Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, February 1999, Volume 7(1), Pages 56-63.

4. Chae Y, et al, Subjective and autonomic responses to smoking-related visual cues, The Journal of Physiological Sciences, April 2008, Volume 58(2), Pages 139-145.

5. Franklin TR, Limbic activation to cigarette smoking cues independent of nicotine withdrawal: a perfusion fMRI study, Neuropsychopharmacology, November 2007, Volume 32(11), Pages 2301-2309.

6. Small DM, et al, The posterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex mediate the anticipatory allocation of spatial attention, NeuroImage, March 2003, Volume 18(3), Pages 633-641.

All rights reserved

Published in the USA