Extinction

Extinction is the elimination of conditioned learning over time. With operant conditioning, it begins once reinforcement ends, and with classical conditioning upon presentation of the use stimuli (a use-cue) in the absence of use.

Extinction is the elimination of conditioned learning over time. With operant conditioning, it begins once reinforcement ends, and with classical conditioning upon presentation of the use stimuli (a use-cue) in the absence of use.

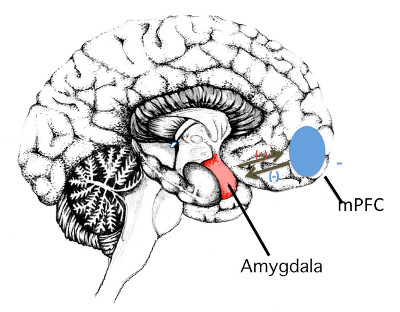

The brain regions most involved in extinction are the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is located immediately above and between your eyes, and the amygdala, two almond-shaped structures located an inch or so behind each eye.[1]

In humans, how long or how many encounters does it take to extinguish a specific conditioned response? Frankly, we don't yet know.

What we do know is that within a week of ending nicotine use that old memory traces linking the bulk of our regular daily cues (each a conditioned stimulus or CS) to nicotine (an unconditioned stimulus or US), are no longer producing crave episodes (a conditioned response or CR).

While we learn through our senses, memory is the maintenance of learning over time.

The biggest scientific debate has been whether cue extinction occurs due to unlearning or new learning. Is extinction the result of old CS-US memory pairing traces between neurons being overwritten, or new CS-noUS memory traces being created?

A growing number of researchers believe that the answer is both.

Studies have found that while extinction does not erase the original CS-US memory trace, extinction somehow inhibits it, while at the same time new memories are generated documenting encounters with a former use-cue, where use did not occur.[2]

Thank goodness that we don't need to be molecular biologists with an understanding of how phosphatases and kinases form and extinguish long-term memories in order to break free.[2]

What's important is appreciation that extinction begins almost immediately upon ending use, and that reinstatment of operant conditioning and at least one conditioned use-cue is always just a puff away.

But how do we resist in standing firm in saying "no" to years of use reinforcement and an unknown number of subconscious use pairings?

Once triggered, how do we control the impulse to use? How do we muster what researchers call inhibitory control?

Just one extinction opportunity at a time.

Getting it done

An obvious problem in studying use-cue extinguishment is that scientists are left guessing as to subconscious use associations. Most studies resort to showing pictures or images of suspected use-cues.[3]

Real-world empirical evidence suggests that, like the traveling hypnotist telling subjects to ignore a prior behavioral suggestion upon waking, that when combined with dreams, desires, and higher priorities, that a single use-cue encounter with a "no more, never again" mindset can immediately disable a cue.

This doesn't mean that encountering the exact same nicotine use cue the day after extinction won't cause the conscious mind to briefly focus or even fixate upon "thoughts" of wanting.

It means that the first encounter where our consciousness shouts to our subconscious that use has ended for good, may be sufficient to prevent a subsequent encounter from generating a subconsciously triggered crave episode.

Recovery is about re-learning to engage in every activity we did as users but without nicotine.

Ending use almost immediately compels us to confront and extinguish all use conditioning related to survival activities such as breathing, eating, sleeping, and using the bathroom.[4]

While essential to feed the kids and get them off to school, early fears of encountering crave triggers can motivate postponement, at least briefly, of non-essential activities such as housework or proper personal hygiene.

Some try to hide from life. But, not without a price. Ignoring a dirty house or tall grass may breed escalating internal anxieties or cause needless family frictions.

Joel cautions that aside from threatening our livelihood and making us look like a slob, if we attempt to hide and avoid confronting use cues associated with non-survival activities for too long, we may become so intimidated that we begin believing that we'll never be able to engage in the activity again.

Then, there are non-mandatory activities such as partying, dating, nurturing relationships, television, the Internet, sports, hobbies, and games. The only way to extinguish cues associated with any activity is to engage in the activity, confront the cue, and reclaim that aspect of life.

And reclaiming life isn't going to happen by me, Joel, or this book talking about it. It'll happen by you going out into and experiencing and living your day.

Admit it. Recovery anxieties generated by delay in reclaiming any aspect of life are totally within our ability to eliminate.

Still proud, years after breaking free I walked into a convenience store to pay for gas while wearing my "Hug me I stopped smoking" tee-shirt. The clerk behind the counter asked if it were true.

While literally surrounded by cigarette packs, cartons, oral tobacco products, and cigars he asked, "Did you really quit?" "Yes," I said. "After thirty years and being up to three packs-a-day!"

"I haven't had a cigarette for a week," the clerk replied. You could feel and see his smiling pride. While heading for the door I heard the lady who had been behind me say, "Two packs of Marlboro Lights, please."

Think about the clerk's first day on the job after his last nicotine fix. Imagine your livelihood requiring you to repeatedly reach for and handle cigarettes, a proximate and conditioned use cue for nearly all.

Yes, his first time may have triggered a cue-induced mini anxiety attack. If so, what are the chances he was so busy that it peaked and passed before he had an opportunity to take a break and quiet it by relapse?

While subsequent sales may have caused urges associated with conscious thoughts of wanting, the difference was the absence of an uncontrollable anxiety episode. This time, the intensity and duration of the experience was substantially within his ability to control.

But be careful here. Some conditioned use cues are so similar to others that we fail to grasp their distinction. For example, the Monday through Saturday newspaper may have only been associated with inhaling nicotine once, while Sunday's paper is much thicker and may have required replenishment two or more times to read.

Reward Deficiency Syndrome

Need another reason for seeing the extinction of use conditioning as good and wonderful? There are two theories as to the consequences of nicotine hijacking dopamine pathway-related learning: the incentive sensitization theory and reward deficiency syndrome theory. [5]

As its name suggests, incentive sensitization is the sensitivity consequences upon natural dopamine pathway learning due to the frequency of compliance with nicotine use cues. Research suggests that while heightened incentive is given to nicotine use, it results in diminished sensitivity to life's non-use cues.

The reward deficiency syndrome theory is even worse. Here, research supports the prospect that use-conditioning compliance causes chronic brain reward pathway deficits, with diminished activation in response to both nicotine use-cues and life's non-use cues.

Unfortunately, the lastest research supports the reward deficiency syndrome theory. It's consistent with needing a bit more nicotine over time (increased tolerance), in order to more frequently experience diminished sensitivity.

"[A]ddicts have a general deficit in the recruitment of brain reward pathways, resulting in chronic hypoactivation of these circuits in response to both drug- and nondrug-related rewards," with the degree of dopamine pathway sensitivity disruption mirroring the severity of dependence. [5]

Has addiction to nicotine caused you to favor your favorite food less? [6] Just one more reason for fully reclaiming our brain as quickly as possible.

References:

2. Todd TP, Vurbic D, Bouton ME, Behavioral and neurobiological mechanisms of extinction in Pavlovian and instrumental learning, Review, Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, Feb 2014, Volume 108, Pages 52-64.

3. Unrod M. et al, Decline in cue-provoked craving during cue exposure therapy for smoking cessation, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, March 2014, Volume 16(3), Pages 306–315.

4. Spitzer J, Alcohol and quitting smoking, June 9, 2001, https://whyquit.com/joels-videos/alcohol-and-quitting-smoking/

5.Lin X, et al, Neural substrates of smoking and reward cue reactivity in smokers: a meta-analysis of fMRI studies, Translational Psychiatry, 2020, Volume 10:97

6. Jastreboff, A. M. et al. Blunted striatal responses to favorite-food cues in smokers, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Jan. 2015, Volume 146, Pages 103–106.

All rights reserved

Published in the USA