Chantix / Champix Worth Questioned

John R. Polito January 6, 2011

Marketed in Australia and the rest of the world as Champix and in the United States as Chantix, according to Professor Raoul A. Walsh, during 2008 the Australian government paid for 368,924 prescriptions of varenicline (252,618 4-week initiation and 116,306 8-week continuing), yet to this day it has absolutely no idea how many smokers actually quit.

Professor Walsh is concerned that the $93 million the Australian government paid for varenicline between January 2008 and October 2009 is 58% more than the $59 million that the government has budgeted for youth smoking prevention over the four year period ending in 2013.

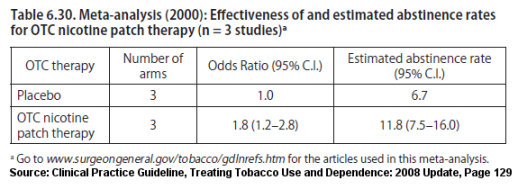

His letter notes that when results from varenicline's five drug approval studies are combined and averaged that the absolute difference between varenicline and placebo quitting rates at one year was only 10.8%, a rate similar to rates seen among over-the-counter nicotine replacement product users (the nicotine gum, patch and lozenge).

A 2008 study (Aubin) pitted varenicline against the nicotine patch. Although not cited by Professor Walsh, it backs his assertion. In examining the actual percentage of successful quitters at two different time points, the study found "no significant differences" between Champix and nicotine patch quitting rates at either 6 months (varenicline 38.6% vs. patch 34.1%) or one year (varenicline 34.8% vs. patch 31.4%).

Aubin's finding was mirrored in Tsukahara 2010 which also pitted Chantix against the nicotine patch. There, the study's abstract openly declares that "no significant difference in abstinence rates was observed between the 2 groups over weeks 9-12 and weeks 9-24."

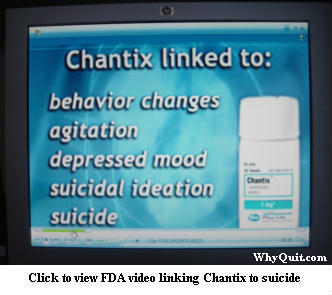

The obvious question becomes, since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already linked Chantix to thousands of serious adverse events, including suicide, if your chances of quitting with Chantix are no better than with the nicotine patch or gum, why take the risk?

The obvious question becomes, since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already linked Chantix to thousands of serious adverse events, including suicide, if your chances of quitting with Chantix are no better than with the nicotine patch or gum, why take the risk?

Smokers visiting Pfizer's Chantix website are hit with the assertion that, "Chantix is proven to work. In studies, 44% of Chantix users were quit during weeks 9 to 12 of treatment (compared to 18% on sugar pill)."

According to Professor Walsh, "there are a number of reasons why varenicline may be less effective under 'real world' conditions than in research trials." He notes that Chantix clinical trials excluded all smokers having major medical conditions, that their varenicline was free, and that participants were paid for their time and travel.

Does Pfizer's unqualified boast of a 44% Chantix quitting rate constitute an unfair and deceptive bait and switch marketing tactic? I ask because it fails to mention that the biggest difference between clinical trials and real-world use is the record number of counseling and support sessions received by participants in Pfizer's clinical trials. As Professor Walsh notes, they were "much higher than in most primary care settings."

"For example," says Professor Walsh, "in the influential Jorenby et al trial, subjects had a total of 28 contacts (eight telephone, 20 personal) with study personnel, of which 18 involved some counselling. Another typical trial involved 24 contacts including counselling on 13 occasions."

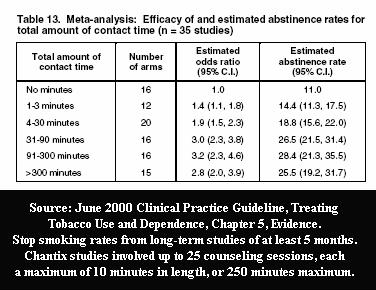

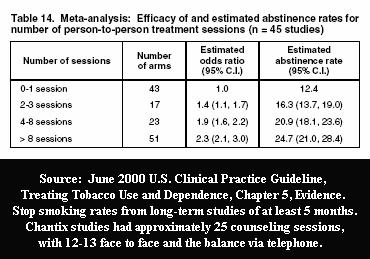

What isn't mentioned by Professor Walsh is that according to June 2000 U.S. Guideline evidence Tables 13 and 14, the number and duration of counseling sessions and support contacts employed in Pfizer's Chantix / Champix trials could account for nearly all successful quitting seen among Chantix users at long-term follow-up.

For example, participants received 25 counseling sessions of up to 10 minutes each in the 2008 Aubin Chantix versus nicotine patch study, which found "no significant differences" in long-term point prevalence quitting rates, yet both groups exceeded 30% at 6 months (38.6% vs. 34.1% respectively). According to Table 6.30 of the 2008 U.S. Guideline Update, the average 6 month point prevalence quitting rate for the nicotine patch when used as a stand-alone quitting aid without counseling or support is three times lower at 11.8%.

The billion dollar question is why the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved allowing Pfizer to design its drug approval studies so as to include a record number of counseling/support sessions, when prescription NRT and Zyban use history should have taught the FDA that relatively few quitters would seek or use counseling or support.

Shockingly, to this day, with thousands of varenicline users worldwide reporting serious adverse events, no person on earth knows Chantix or Champix's real-world effectiveness as a stand-alone quitting product. It isn't being studied. But why?

As noted by Professor Walsh, "in Australia, the [government's subsidized medication] guidelines state that varenicline should be restricted to patients entering a comprehensive counselling programme," but no data is being collected to determine whether or not that's happening.

"Clearly, there is a need for high-quality research to evaluate the probable population impact of this cessation intervention," wrote Professor Walsh. He recommends using a "tiny proportion of varenicline prescription spending" to fund data collection so that valid estimates of the long-term effects of varenicline on cessation rates can be determined.

U.S. Sticking Its Head in the Sand

U.S. health officials appear to be going out of their way to not analyze available data so as to discover whether or not FDA approved quitting products such as Chantix are effective in real-world use. An August 2010 Freedom of Information Act Request (FOIA) sought all survey results in which smokers were asked how they quit smoking.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) responded to the FOIA request on September 28, 2010. It noted that the National Cancer Institute does sponsor three surveys that "include questions asking smokers how they quit smoking," but that the NIH search "did not produce any hard-copy records or 'short-summary report'" of findings.

The NIH FOIA office's assertion that no reports exist stands in stark contrast to a February 8, 2007 front-page Wall Street Journal article which featured a non-published National Cancer Institute survey in which those quitting without medications actually did slightly better, long-term, than those using them.

The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health (ASH) responded to the FOIA request on October 12, 2010 stating that it had "conducted a search along with the Office of the Surgeon General and could not locate records responsive to your request."

England's 4 Week Blinders

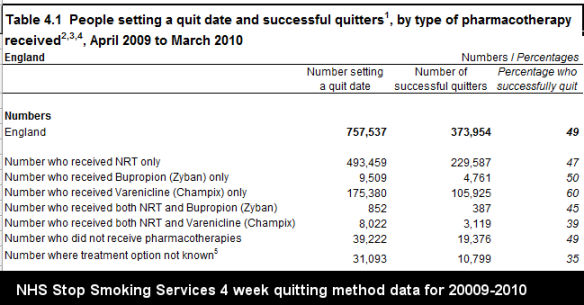

More varenicline quitting data is generated by England's National Health Service (NHS) Stop Smoking Services than any other nation. The problem is that it's almost worthless.

A pharm industry dream come true, the NHS declares total quitting success and ends follow-up of stop smoking program participants at 4 weeks. It does so knowing that the brain dopmaine pathways of NRT, Zyban and Champix users have another 4 to 8 weeks of stimulation by quitting products before attempting to end product use and adjust to natural stimulation.

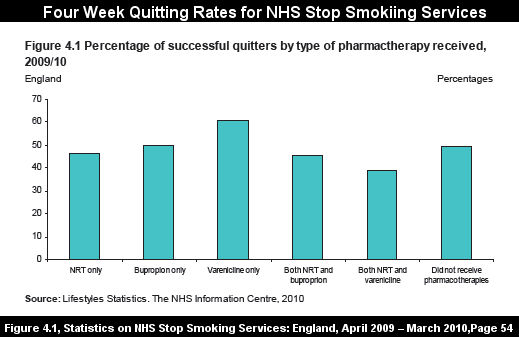

Before looking at the most recent four-week NHS 2009-2010 quitting method data, reflect on Pfizer's website assertion that "44% of Chantix users were quit during weeks 9 to 12 of treatment (compared to 18% on sugar pill)." With that in mind, attempt to predict both the the 4 week quitting rate for both NHS varenicline users and for those quitting without use of any quitting product, cold turkey quitters.

While Pfizer's website suggests quitters can expect 2.4 times better odds at 12 weeks than among those taking sugar pills, as shown by the above graph, last year NHS varenicline users performed only about 20% better than non-medication quittters at 4 weeks.

Cold turkey quitters become nicotine-free and move beyond peak withdwrawal within 72 hours of ending all nicotine use. It's then that the brain is able to begin restoring a4b2-type nicotinic receptor sensitivities and down-regulating receptor numbers to levels seen in non-smokers.

NRT, bupropion and varenicline each stimulate, desensitize and keep dopamine pathway receptors un-regulated. It isn't until treatment stops and stimulation ends that medication users are compelled to adapt to the changes already navigated by successful cold turkey quitters.

While the U.S. government suppresses and hides almost all real-world quitting method data - findings it knows conflict with official cessation policy which mandates quitting products use by all quitters - the U.K. pretends the fiction that those still undergoing medication treatment have already successfully quit.

Look closely at the above NHS 2009-2010 quitting data, while keeping in mind

that in the Aubin study, Chantix and NRT point prevalence quitting rates were nearly the same at both 6 months and one year. Now contrast that to the only study to examine long-term NHS Stop Smoking Services rates, the 2005 Ferguson study (see bottom of Table 6). There, non-medication quitters did substantially better than medication quitters. Varenicline use wasn't seen in the Ferguson study as it did not arrive on the market until May 2006.

that in the Aubin study, Chantix and NRT point prevalence quitting rates were nearly the same at both 6 months and one year. Now contrast that to the only study to examine long-term NHS Stop Smoking Services rates, the 2005 Ferguson study (see bottom of Table 6). There, non-medication quitters did substantially better than medication quitters. Varenicline use wasn't seen in the Ferguson study as it did not arrive on the market until May 2006.

Will Pfizer's financial muscle and influence permit real-world evaluation of questions as fundamental as whether or not Chantix and Champix are more effective than unassisted cold turkey quitting?

Aside from the obvious problem of motivating entrenched health bureaucrats to care whether these quitting products actually work, the primary problem is finding truly independent cessation researchers who are not already financially beholden to the quitting product industry. Stay tuned.

No Copyright - This Article is Public Domain

John R. Polito is solely responsible for the content of this article. Any factual error will be immediately corrected upon receipt of credible authority in support of the writer's contention. E-mail comments to john@whyquit.com

Knowledge is a Quitting Method