The nicotine patch, gum and lozenge: mounting evidence of a sham upon smokers

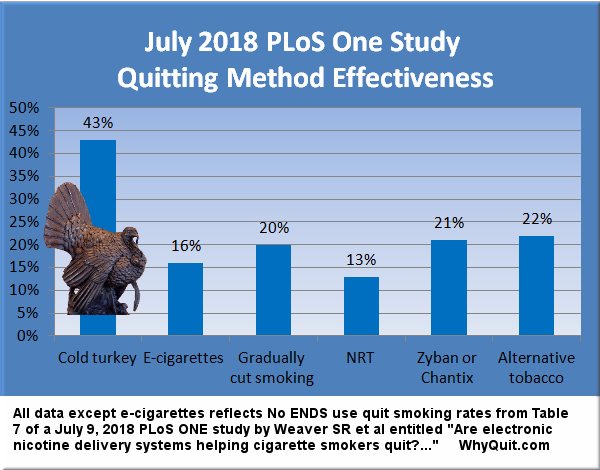

According to "real-world" quit smoking surveys, smokers quitting entirely on their own -- without any products, services or procedures -- are doing as well or better than those attempting to quit by relying upon expensive over-the-counter (OTC) nicotine replacement therapy products (NRT) such as the patch, gum or lozenge.

A recently published survey of Maryland smokers concludes that as "compared to nonusers, ever users of NRT were less likely to have stopped smoking."

NRT pharmaceutical companies continue to advertise that the nicotine patch, gum and lozenge will double a smoker's chances of quitting, while fully aware that there is absolutely no "real-world" use evidence supporting any advantage for NRT. Instead, they rely upon odds ratio victories over quitters using placebos in formal double-blind clinical studies, studies that a June 2004 blinding assessment study found were not blind as claimed.

The Maryland study was published in the January 2005 edition of the Journal of Addictive Diseases (Vol. 24, Number 1). "Relatively little is known about the use of nicotine replacement therapy in the general population," contended the study's authors.

The study followed 1,954 Washington County, Maryland residents who were current smokers in 1989. In 1998, each was asked to complete a questionnaire providing information on their smoking, quitting and NRT use. Over the nine years surveyed, 36% of the 1,954 smokers had attempted quitting while using the nicotine gum or patch. During the same nine year period, 39% of the group who had never used any NRT product successfully quit while only 30% of those who had ever used NRT quit.

In speculating on replacement nicotine's "real-world" defeat, the authors suggest that perhaps those who choose to use NRT are more dependent and less likely to quit. But the study's own cigarettes "smoked per day" data does not indicate significant NRT use differences. They show that NRT was used by 39% of those smoking 15-24 cigarettes per day, 44% of those smoking 25 to 34 per day, and 45% who smoked greater than 35 cigarettes per day.

A potential explanation not discussed by the authors is that all double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials may have been fatally flawed from the beginning; that it may be nearly impossible to blind a study involving a psychoactive chemical. Instead of NRT's "double your chances" conclusion being "science-based," it may be "junk-science" grounded in mountains of missed junkie-thinking. But how?

A June 2004 study in Addictive Behaviors examined 73 formal clinical studies and concluded that they were not blind as claimed. It found that a significant percentage of participants could accurately guess whether or not their nicotine delivery device was an inert placebo or the real thing.

Entitled "The blind spot in nicotine replacement literature," the study presents authority indicating that smokers with any history of quitting may learn and discover what it feels like for their nicotine induced psychoactive dopamine/adrenaline high to be present or absent. If true and acted upon, it's a lesson that could destroy the conclusions of any study attempting to fool them.

The blinding assessments of the few clinical NRT studies that did assess study blindness (only 17 of 73) were so poorly conducted that we simply do not know whether or not frustrated or fulfilled expectations of receiving weeks or months of free nicotine products played a role in handing NRT an unearned "double your chances" odds ratio victory. What we do know is that 71% of NRT studies assessing blindness failed their own blinding assessment.

We also know that an extremely large percentage of placebo group members (often above 50%) grew frustrated and relapsed within the first two weeks. What we do know is that no NRT blinding assessment was conducted while the participant's beliefs about group assignment and their reasons for relapse were still fresh in their mind. Twelve studies waited three months before interviewing participants and four waited an entire year.

The FDA approved prescription nicotine gum in 1984 and the prescription patch in 1992. Both became available over-the-counter in 1996. The Maryland survey's finding of absolutely zero advantage for NRT is consistent with all "real-world" quitting surveys conducted since 1996.

In September 2002 a California survey published in the Journal of the America Medical Association boldly declared "NRT appears no longer effective in increasing long-term successful cessation in California smokers." Since then, Minnesota, London and Quebec surveys also found no advantage for NRT.

In light of a growing body of "real-world" evidence, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should immediately demand that the NRT industry prove that serious blinding failures did not impact the outcome of clinical NRT trials or threaten to pull approval unless they do.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission, responsible for truth in national advertising, should demand that the pharmaceutical industry either prove that OTC NRT products are twice as effective in helping real-world smokers quit, or immediately cease any and all marketing that falsely leads smokers to believe that it is. In fact, the FTC should require disclosure that no "real-world" survey of OTC NRT products to date has found any long-term advantage (at least six months) for those using replacement nicotine.

[This chart was added to this 05/30/05 article on 08/16/18. See Related reading to see additional findings since 2005.]

Today, more than 50% of all smokers have attempted quitting while using replacement nicotine at least once. If NRTs "double your chances" promise were true, we should have seen a massive increase in U.S. cessation rates. Instead, since the arrival of OTC NRT, national cessation rates have almost ground to a halt.

While those addicted to smoking nicotine die in record numbers, Philip Morris USA continues to tell them that a key to quitting is to buy more nicotine - replacement nicotine.

What Philip Morris's quit smoking website will never disclose is that those relying exclusively upon the OTC nicotine patch have a 93% chance of relapsing to smoking within six months. What it will not tell them is that two studies have shown that if they've already used the patch one time that their odds of relapse and defeat during a second attempt increase to almost 100%.

It's time that those charged with protecting American consumers begin doing their job. Needless lives are being lost and it's beyond time that we started investigating how many and why.