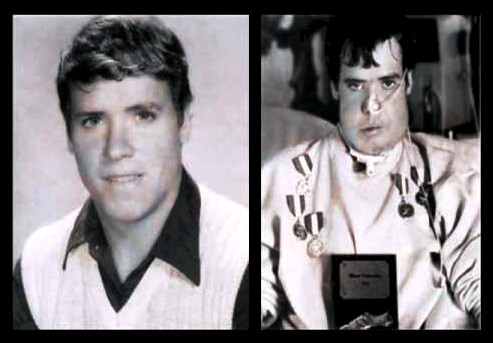

Nineteen-year-old Sean Marsee's tobacco message

Talihina High School's most outstanding athlete, Sean Marsee had won 28 track medals in the 400 meter relay while running the anchor leg. His classmates honored him with a walnut plaque. After a ten month battle with rapidly spreading cancer that started on his tongue, Sean Marsee died at age 19.

A smokeless tobacco user since age 12, Sean refused to believe his mother's warnings that tobacco was hazardous, smoke or no smoke.

It was early on February 25th. Sean Marsee smiled a tired smile at his sister, pointed his index finger skyward and an hour later, at age 19, Sean Marsee was dead.Just ten months earlier, Sean, an 18 year-old high school senior and star of the school track team, was just a weekend away from competing in the state track finals, and a month from graduation.

It was then that Sean opened his mouth and showed his mother an ugly sore on his tongue. His mother, a registered nurse, took one look and felt her heart sink.

A user of smokeless chewing tobacco and snuff since age 12, rarely was Sean without a dip. Living from nicotine fix to nicotine fix, he went through a can of snuff every day and a half. When Sean's mother finally discovered his secret she hit the roof. She tried explaining just how hazardous that tobacco was for him, smoke or no smoke, but Sean refused to believe her.

He argued that other boys on the track team were dipping. He argued that his coach knew and didn't seem to care. He argued that high profile sports stars were using and marketing smokeless tobacco. How could it be dangerous, he pleaded.In the end, his mother simply dropped the subject.

But now, an angry red spot with a hard white core, about the size of a half-dollar, was being worn by his tongue. "I'm sorry, Sean," said Dr. Carl Hook, the throat specialist. "It doesn't look good. We'll have to do a biopsy."Sean was stunned.

Aside from his addiction to nicotine, he didn't drink, he didn't smoke and he took excellent care of his body; watching his diet, lifting weights and running five miles a day, six months a year.Now this. How could it be? "But I didn't know snuff could be that bad for you," Sean said.

"I'm afraid we'll have to remove that part of your tongue, Sean," Dr. Hook said. The high school senior was silent. "Can I still run in the state track meet this weekend?" he finally asked. "And graduate next month?" Dr. Hook nodded.

On May 16th, Dr. Hook performed the operation. More of Sean's tongue had to be removed than was anticipated.Worse yet, the biopsy results were back and the tumor tested positive for cancer. Arrangements were made for Sean to see a radiation therapist. But before therapy began, a newly swollen lymph node was found in Sean's neck. It was an ominous sign that the cancer had spread. Radical neck surgery had now become necessary.

Dr. Hood gently recommended to Sean that he undergo the severest option: removing the lower jaw on the right side, as well as all lymph nodes, muscles and blood vessels except for his artery. There might be some sinking, he explained, but the chin would support the general planes of the face.

His mother began to cry. Sean was being asked to approve his own mutilation. This was a teenager who was so concerned about his appearance that he'd even swallow his dip rather than be caught spitting tobacco juice.

They sat in silence for ten minutes. Then, dimly, she heard him say, "Not the jawbone.Don't take the jawbone."

"Okay, Sean, " Dr. Hook said softly."But the rest; that's the least we should do." On June 20th Sean underwent his second surgery. It lasted eight hours.

At school, 150 students and teachers assembled in June to honor their most outstanding athlete. Sean could not be there to receive their award. His Coach and his assistant came to Sean's home to present their gift, a walnut plaque. They tried not to stare at the huge scar that ran like a railroad track from their star performer's earlobe to his breastbone. Smiling crookedly out of the other side of his mouth, Sean thanked them.

With five weeks of healing and radiation therapy behind him, in August Sean greeted Dr. Hood with enthusiasm, plainly happy to be alive.Miraculously, Sean had snapped back. "He really believes his superb physical condition is going to lick it," Dr. Hook thought."Let's hope he's going to win this race too."

But in October Sean started having headaches. A CAT scan showed twin tentacles of fresh malignancy, one snaking down his back, the other curling under the base of his brain. In November, Sean underwent surgery for the third time. It was the jawbone operation he had feared - and more.

After 10 hours on the operating room table, he had four huge drains coming from a foot long crescent wound, a breathing tube sticking out of a hole in his throat, a feeding tube through his nose, and two tubes in his arm veins. Sean looked at his mother as if to say, "My God, Mom, I didn't know it was going to hurt like this."

The Marsees brought Sean home for Christmas. Even then, he remained optimistic until that day in January when he found new lumps in the left side of his cheek. His mother answered the phone when the hospital called with the results of the biopsy. Sean knew the news was bad by her silent tears as she listened.

When she hung up, he was in her arms, and for the first time since the awful nightmare started, grit-tough Sean Marsee began to sob. After a few minutes, he straightened and said, "Don't worry. I'm going to be fine." Like the winning runner he was, he still had faith in his finishing kick.

One day Sean confessed to his mother that he still craved his snuff. "I catch myself thinking," he said, "I'll just reach over and have a dip." Then he added that he wished he could visit the high-school locker room to show the athletes "what you look like when you use it." His appearance, he knew would be persuasive. A classmate who had come to see him fainted dead away.

Shortly before Sean's death he told his mother that there must be a reason that God decided not to save him. Sean's mother believes that Sean's legacy is in having his story spread and hopefully "keeping other kids from dying."When Sean became unable to speak, a friend asked him if there was anything he wanted to share with other young athletes. With pencil in hand Sean wrote, "Don't dip snuff."

On the morning of February 25th, Sean Marsee, age nineteen, exhaled his last breath.

Compiled by John R. Polito, Founder WhyQuit.com, June 2000

Share this article