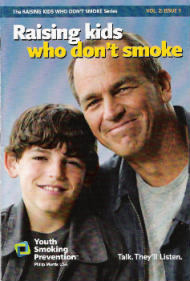

Philip Morris revises "Raising kids who don't smoke"

Parents wanting to teach their child the unabridged truth about smoking might be wise to select a teacher other than Philip Morris USA. Imagine the internal mismatch tug-o-war with one finger of a tobacco company conducting a campaign to protect underage youth from smoking, while all other fingers fully appreciate that children and teen smokers represent nearly 90% of all new customers.

Philip Morris has just released a revised edition of its 2003 parent training booklet entitled "Raising kids who don't smoke." The reworked sixteen page parent lesson guide deletes all references to the word "nicotine" and erases an important warning that youth can become hooked within a few days.

Philip Morris has just released a revised edition of its 2003 parent training booklet entitled "Raising kids who don't smoke." The reworked sixteen page parent lesson guide deletes all references to the word "nicotine" and erases an important warning that youth can become hooked within a few days.

According to page four of the 2003 version, "The younger people are when they start smoking, the more likely the are to become strongly addicted to smoking nicotine." The revised language reads, "The younger people are when they start smoking, the more likely they are to develop a long-term addiction."

Absent under page four's "Addiction" heading is the 2003 warning that, "Symptoms of addiction (having strong urges to smoke, feeling anxious or irritable, or having unsuccessfully tried not to smoke) can appear in teens and preteens within ...only days after they become occasional smokers." It now reads, "Some teens and preteens report signs of addiction with only occasional (non-daily) smoking."

Why would Philip Morris not want to teach parents and youth that smoking is a true chemical dependency (upon nicotine) and how quickly a child can permanently lose their freedom (within days)? Why would it instead leave them with vague undefined generalities such as "some" teens report "signs" of addiction after "occasional" smoking. What percentage is "some" and how soon is "occasional?"

Since May 7, 2005, WhyQuit.com has conducted an informal online smoking initiation survey. It asks smokers, "when you first started smoking, how many cigarettes did you smoke before you sensed your brain issue an urge or crave command to smoke again? A second related autonomy question asks how long they smoked before sensing their first crave.

Roughly half responding couldn't remember. But among the 908 who claimed to recall the number of cigarettes they smoked before the craves started, 27% claim to have sensed their first crave after smoking just 1 to 3 cigarettes and another 16% after smoking 4 to 6. When asked the length of time before their first crave, 24% experienced it within 1 to 2 days of starting to smoke, and another 11% within 3 to 4 days.

Are parents and teens being provided accurate dependency risk assessment information when told that "some" youth smokers report "signs" of addiction with only occasional smoking, when up to 43% may begin exhibiting loss of autonomy symptoms after smoking fewer than seven cigarettes, and when for 35% the craves may begin within 4 days?

Can a teen be expected to fairly and accurately evaluate the risk of becoming addicted to smoking nicotine when tobacco companies use vague risk language such as "some" or "most"? Can a teen be expected to appreciate that smoking involves true chemical dependency when those teaching the lessons go so far as to hide the name of the drug?

Page eight of the 2003 edition advises parents to, "Ask about some of the symptoms of nicotine addiction" while page eight of the 2005 edition reads, "Ask about some of the symptoms of cigarette addiction."

Imagine teaching a dependency recovery course on alcoholism and never mentioning alcohol but instead referring to "bottle addiction." Imagine a heroin recovery program deleting the word heroin and talking about "needle addiction." The cigarette is an extremely dirty and fast drug delivery vehicle for nicotine - one of the most addictive substances on earth.

What percentage of first time youth smokers -- even adding in those who don't inhale -- become addicted? What percentage of daily teen smokers are already chemically dependent? Should Philip Morris expect youth to make intelligent risk decisions when it fails to warn them of actual risks?

Page 4 of the 2003 version of "Raising kids who don't smoke" cites a 1997 CDC report as stating that "more than one third of all kids who try smoking go on to smoke daily" (actual rate 36%). Sadly, the 2005 revision deletes this CDC youth risk reference entirely.

Almost as important is the missing risk lesson about the percentage of youth smokers who are already hooked solid. Might a teen's decision to take that first fateful puff be impacted by awareness that the student offering them nicotine is likely already addicted themselves?

Although a recent study found that 86.8% of students who smoke nicotine at least once daily are already dependent under DSM-IV nicotine dependency standards, Philip Morris brochures simply cannot teach this lesson without being accused of unfair and deceptive cigarette marketing practices.

For example, take Philip Morris' best selling brand of cigarettes, Marlboro. Marlboro's sales theme is "Come to where the flavor is." If in fact almost all Marlboro smokers (about 90%) are chemically addicted to smoking nicotine, and their now de-sensitized brains are occupied by millions of extra nicotinic receptors in eleven different brain regions, with diminished receptor counts in other regions, then is it honest to teach America's youth that adult smokers smoke for flavor or taste?

Philip Morris' booklet contains no awareness lesson about looking to see whether or not a smoking friend inhales each puff of smoke into their lungs. If 100% of taste-buds are in the mouth and none in the lungs then why would someone who smokes for flavor or taste need to suck each puff of smoke deep into their lungs and briefly hold it there, instead of holding the smoke in their mouth?

Why would Philip Morris skip lessons on how rapid blood circulation through the lungs is nicotine's eight second path to the brain? How could a corporation in the nicotine addiction business ever tell students the truth, that smoking nicotine isn't just "addictive" but extremely addictive and that once hooked it's as permanent as alcoholism?

Flavor, taste, excitement, adventure, rebellion, to look more adult, to look slim like Virginia, or make new friends, the fact that smoking nicotine produces alert dopamine adrenaline intoxication allows those pushing it to pretend that those chemically addicted to it continue to buy it for every reason imaginable except the truth.

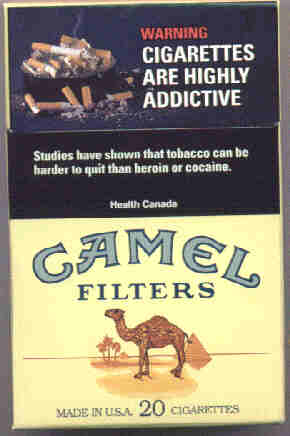

In Canada, one-half of the front and back face of random packs of Marlboro carry a mandatory label which reads, "WARNING - Cigarettes are highly addictive - Studies have shown that tobacco can be harder to quit than heroin or cocaine.

"If smoking is "highly addictive" and here in the U.S. Philip Morris youth smoking prevention literature never once mentions smoked nicotine's degree of addictiveness, how can it possibly assert that it is providing U.S. youth with accurate risk assessment information?

The 2003 version asserted that "almost 9 out of 10 lung cancer deaths are caused by smoking cigarettes." The 2005 version reads, "most cases [of lung cancer] are caused by smoking." Isn't it rather serious when a tobacco company knowingly teaches parents and youth that as few as 51% of lung cancers ("most") are caused by smoking when in truth it's the cause of almost all lung cancers? What motivated this change?

The 2003 version contains a number of photographs of teens and/or parents in which the parent or teen is quoted, their name given and their state of residence identified. Amazingly, photographs in the 2005 version use a number of identical quotes, names and home states as those pictured in the 2003 version, when the person pictured in the 2005 booklet is clearly different. Page 5 of each booklet quotes Mike from California. It is hard not to notice that their hair and complexions are different.

The 2003 version contains a number of photographs of teens and/or parents in which the parent or teen is quoted, their name given and their state of residence identified. Amazingly, photographs in the 2005 version use a number of identical quotes, names and home states as those pictured in the 2003 version, when the person pictured in the 2005 booklet is clearly different. Page 5 of each booklet quotes Mike from California. It is hard not to notice that their hair and complexions are different.

The quote on page 13 of both the 2003 and 2005 editions reads, "I've told my kids that starting to smoke was the worst mistake I've every made in my life. Ever since they started learning in school about the health risks of smoking, we've talked about it. Of course, they want me to quit, and they see how difficult it is to kick the habit."

Two points about the above quote. Least significant is the rather amazing coincidence that Marge, a Caucasian mom from Iowa pictured with her daughter, (2003), and Mark, an Hispanic looking dad pictured with his daughter (2005), have identical quotes.

Two points about the above quote. Least significant is the rather amazing coincidence that Marge, a Caucasian mom from Iowa pictured with her daughter, (2003), and Mark, an Hispanic looking dad pictured with his daughter (2005), have identical quotes.

More importantly is Philip Morris' lesson to teens that smoking is just a "habit." What is a teen's understanding of the word habit and how long does it take to establish one? Can they get away with doing an activity at least a few times without the risk of forming a habit?

Glaringly, the booklet does not describe nicotine withdrawal or the recovery process. Use of the word "habit" to describe a parent's frequent smoking creates an obvious definition conflict in the average child's mind and muddies their distinction between a habit (conditioning) and an addiction (true chemical dependency).

Would a teenager experience hurtful anxieties, powerful mood shifts, an inability to concentrate, depression, time distortion, fatigue, headaches, chest tightness, nausea, and constipation if they suddenly stopped using cuss words or started using their turn signal while driving the family car? It not only diminishes risk in the mind of a teenager, it comforts the nicotine dependent parent reading the comment, in that the only admission they make is that they suffer from a "nasty little habit."

The booklets are ripe with such double-talk. Under the 2003 page eight heading, "If your child already smokes," parents are advised to "...ask your child about his smoking. How long has he been smoking? Why? There is a chance that, if your child has been smoking for a while, he may be addicted."

Gone is the recommendation to directly ask your child if they smoke. "Without accusing, talk about situations, people or feelings that might be encouraging him to smoke."

But double-talk isn't just between versions but within the revised booklet itself. For example, if you find that your child is smoking, page 8 advises you to "resist the urge to punish or shame him." But in the preceding paragraph labeled "Set the rules" it states, "Tell your child the consequences for smoking in your family, and make sure you follow through on them." Page 9 advised parents to, "Talk about the house rules and why you set them, and talk about the consequences of breaking them."

Imagine a teen citing page 8, paragraph 3 of Philip Morris' 2005 version of "Raising kids who don't smoke" in order to escape punishment for having smoked.

If Philip Morris' youth smoking prevention campaign had been effective these past two years wouldn't we expect it to be sharing figures to substantiate youth smoking reduction rates? Philip Morris' 3rd quarter 2005 earnings press release states, "Philip Morris USA achieved a retail share of more than 50%, driven by Marlboro's record share, and strong income growth."

All available evidence suggests that Philip Morris' corporate responsibility youth smoking prevention campaign is an extremely thin facade built of half-truths, behind which it's business as usual, or better than usual. Has the return of Philip Morris to television commercials with its corporate image "trust us" campaign, and almost daily reminders to youth about not smoking, actually fostered greater youth smoking curiosity, with a corresponding increase in smoking?

All available evidence suggests that Philip Morris' corporate responsibility youth smoking prevention campaign is an extremely thin facade built of half-truths, behind which it's business as usual, or better than usual. Has the return of Philip Morris to television commercials with its corporate image "trust us" campaign, and almost daily reminders to youth about not smoking, actually fostered greater youth smoking curiosity, with a corresponding increase in smoking?

Do recommendations like, "stress that smoking is for adults only," "make it difficult for minors to obtain cigarettes," and "stress that smoking is dangerous" sound harmlessly familiar? Take a look at a once secret 1991 Philip Morris document called the Archetype Project that strongly suggests that Philip Morris' youth smoking prevention campaign is really an adulthood initiation campaign being used to harvest youth smokers.

The Archetype Project reads like some conspiracy theory, doesn't it. It only gets worse when you see who sought the confidentially agreement on behalf of Philip Morris, Carolyn Levy. In 1993 Ms. Levy was appointed the first head of Philip Morris' youth smoking prevention department.

The next time you visit your neighborhood convenience store -- which to area youth is the neighborhood candy, chip and soda store -- notice the big Marlboro sign behind the counter that begs children and teens to "Come to where the flavor is."

If Philip Morris truly wanted to act responsibly wouldn't it either pull all interior and exterior marketing signs from neighborhood stores or only sell and market its products inside stores that deny youth access? Wouldn't it voluntarily add Canadian style addiction warning labels to every pack sold instead of waiting for "we the people" to legislate their requirement?

Philip Morris has had a golden opportunity these past two years to demonstrate its seriousness about youth smoking prevention. It has failed.

Related Philip Morris Reading

- Marlboro "Maybe" Archetype Ad Campaign - October 29, 2013 - Is Philip Morris International (PMI) currently toying with neuronal definition imprinting within a child's subconscious mind? View 45 Marlboro "Maybe" ads and contrast the lessons being taught to a 1991 Philip Morris study entitled the "Archetype Project."

- Marlboro maker's report ignores youth addiction - October 22, 2013 - Article reviews how Philip Morris International's 2012 Annual Report ignores discussing PMI's core business, nicotine addiction, or the fact that the vast majority of new regular customers were addicted children and teens.

- Nicotine Patch Inventor Fudges Patch Study Findings - July 12, 2009 - Why would Philip Morris fund a nicotine patch smoking cessation study (see 2004 Funding Agreement)? Although not shared in this article, the answer is simple: PM knows that replacement nicotine is horribly ineffective (see July 2013 Gallup Poll).

- Philip Morris revises "Raising kids who don't smoke" - December 5, 2005 - Why parents wanting to teach their child or teen the unabridged truth about smoking might be wise to select a teacher other than Philip Morris USA

- Philip Morris' "Could your kid be smoking?" - August 8, 2005 - A critical review of Philip Morris USA's third sixteen-page youth smoking prevention brochure entitled, Could your kid be smoking?

- Understanding Philip Morris's pursuit of US government regulation of tobacco, McDaniel, PA, et al, Tobacco Control, Volume 14, Number 3, Pages 193-200, June 2005 (link to free full text article)

- Financial Ties and Conflicts of Interest Between Pharmaceutical and Tobacco Companies - 2002 - a study detailing Philip Morris' uneasy partnership with the pharmaceutical industry, and why you have never and never will hear any nicotine replacement product commerical tell you why you need to quit, because smoking kills.

- Philip Morris' Mission Exploration Project - June 27, 2000 - A 140 page PDF file outlining Philip Morris USA's plan for, in part, transforming itself into a highly respected nicotine pharmaceutical company, the same vision RJ Reynolds had in 1972.

- Philip Morris' Archetype Project - August 20, 1991 - A 16 page PDF file detailing what Philip Morris USA learned from its archetype sessions about imprinting smoking upon the neuronal pathways of a child's brain.