Negative Support

"If this is what you're like not smoking, for God's sake, go back!"

"You're such a basket case, you should just give up!"

"I'm trying but my smoking friends laugh, tell me I'll fail and offer me smokes."

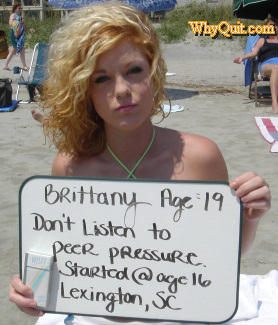

Negative support is likely what got you here. Years later, why let it keep you here?

No person's comment, look, laugh, stare, or offer can destroy our freedom. Only we can do that. According to Joel, most of the time the person making comments or offers such as these have not considered their implications.[1]

It's comparable to telling someone on chemotherapy and in a really bad mood due to hair loss, nausea, and other horrible side effects, that they should get off that stuff because they are so irritable that they are ruining your day, suggests Joel.

"Of course, if analyzed by any real thinking person, the comment won't be made, because most people recognize that chemotherapy is a possible last-ditch effort to save the other person's life. The decision to stop the treatment is a decision to die. So we put up with the bad times to help support the patient's effort to save his or her life."

What's often overlooked, reminds Joel, is that stopping smoking too is an effort to save their life. "While others may not immediately appreciate that fact, the person stopping has to know it for him or herself. Others may never really appreciate the concept, but the person stopping has to."

As Joel notes, such comments are "usually from a spouse, a child of the smoker, a friend, a co-worker, or just an acquaintance. It is much more uncommon that the person expressing it is a parent or even a grandparent. I think that says something."

"Parents are often used to their kids' outbursts and moods, they have experienced them since they were infants. The natural parental instinct is not to hurt them when they are in distress and lash out, but to try to protect them. I think it often carries into adulthood, a pretty positive statement about parenthood."

But Joel has seen where people have encouraged friends or loved ones to relapse and then months or years later the smoker died from a smoking-related disease.

"Sometimes the family member then feels great guilt and remorse for putting the person back to smoking," he says.

But you know what? He or she didn't do it. The smoker did it. Because in reality, no matter what any person said, the smoker had to stop and stay off for herself or himself.

"How many times did a family member ask you to stop smoking and you never listened? Well if you don't stop for them, you don't relapse for them either. You stop for yourself and you stay off for yourself."[1]

"Here, have a cigarette!"

"I left a pack on the kitchen table."

I recall attempts where I hoped smoking friends would be supportive in not smoking around me, and in not leaving their packs lying around to tempt me. While some tried, it usually wasn't long before they forgot.

I recall thinking them insensitive and uncaring. I recall grinding disappointment and intense brain chatter that more than once seized upon frustrated support expectations as this addict's lame excuse for relapse.

Innocent offers of a cigarette or e-cig are far different from malicious ones.

If well-meaning, use the opportunity to educate the person as to the fact that you are a nicotine addict, that you're in recovery, that most smokers end up smoking themselves to death, and that you'd appreciate their support, including not offering or leaving cigarettes or e-cigs laying around.

When declining cigarette offers don't say "No thank you, I can't have a cigarette," suggesting that you really wish you could but that you're depriving yourself of great joy.

As Joel notes, the truth is, you can inhale nicotine and relapse anytime you want. But there's a catch, there's no such thing as just one. Just once and we must accept the consequences of relapsing to our full addiction and going back to our old level of consumption.[2]

An analogy shared by one of Joel's clinic participants, "saying 'I gave up smoking,' is like a recovered cancer patient saying 'I gave up cancer.' You don't give up cigarette smoking, you get rid of it." Instead, we could simply say "I choose not to smoke." [2]

What if you've already politely made the person aware that you're in recovery and they persist in making offers?

Joel recommends that you "look at the person, maybe even with a little bit of sadness and defeat in your eyes, and say to him or her that you can't take the pressure anymore and sure give me a cigarette if you must. When he or she hands you the cigarette, walk over to the nearest garbage can, crumble it up and throw it out."[3]

What happens next? As Joel shares, you can either say nothing and wait to see if they learned from the incident or say, "Thank you, that felt great. Would you like to give me another one?"

"If the person is gullible enough to offer you another, take that one too and repeat the destruction and disposal. Keep it up for as long as the person keeps offering. At some point, you may want to say that this could go a whole lot faster if you would like to give me your pack. You can destroy all of the cigarettes that way in one fell swoop."

What if they leave their cigarettes, e-cig, or other tobacco product lying around after you've kindly asked them not to. Although this sounds harsh, destroying them sends a loud and clear message.

If feeling the need, offer the money needed to replace what you destroyed, letting them know that you're fighting to reclaim your freedom, health, and life and that you'd appreciate their support.

"I'm a bartender. How can I stop when surrounded by smoke and smokers at every turn?"

As I sit here typing in this room, around me are a number of packs of cigarettes: Camel, Salem, Marlboro Lights, and Virginia Slims. I use them during presentations and have had cigarettes within arms reach for nearly 20 years.

Don't misconstrue this. It's not a smart move for someone struggling in early recovery to keep cigarettes on hand. In fact, as reviewed in Chapter 5, it's insane.

But if a family member or best friend smokes, vapes or uses tobacco, or our place of employment sells tobacco or allows smoking around us, if a cashier who sells cigs or a waitress or bartender who cleans up after smokers, we may have no choice but to immediately confront and begin extinguishing tobacco product, smoke, smoker, and vaping cues.

And, just one recovery opportunity at a time, it's entirely do-able!

Millions of comfortable ex-users handle and sell tobacco products as part of their job. You may find this difficult to believe, but I've never craved or wanted to smoke any of the cigarettes that surround me, even when holding packs or handling individual cigarettes during presentations.

Worldwide, millions of ex-smokers successfully navigated recovery while working in smoke-filled nightclubs, restaurants, bowling alleys, casinos, convenience stores, and other businesses historically linked to smoking.

And millions more broke free while their husband, wife, mother, father, child, partner or best friend smoked or vaped like a chimney.

Feeling teased is a normal early recovery emotion. As Joel notes, whether happenstance or intentional, temptation cannot destroy our glory. Only we can do that.

Recovery is about taking back life, not fearing it. Strive to savor, relish, and embrace reclaiming it.

Instead of hiding from the world, speak out, stand up, and take it back. Don't allow negative support to wear you down.

References

- 1. Spitzer, J, Negative Support from Others, February 15, 2001, https://whyquit.com/joel/Joel_04_15_negative_support.html

- 2. Spitzer, J, "No thank you, I can't have a cigarette," https://whyquit.com/joels-videos/no-thank-you-i-cant-have-a-cigarette/ Accessed August 29. 2020.

- 3. Spitzer, J, How to deal with people offering you cigarettes after you have quit, https://whyquit.com/joels-videos/how-to-deal-with-people-offering-you-cigarettes-after-you-have-quit/ Accessed August 29, 2020.