A woman's menstrual cycle lasts an average of 28 days. A complex interaction of hormones causes 80 to 90 percent of women of childbearing years to notice some degree of physical, psychological, or emotional change related to their menstrual cycle.

The most profound symptoms are known as "premenstrual syndrome" or PMS. PMS normally occurs between menstrual cycle days 23-27, subsides once menstruation begins, and is experienced by 30-40 percent of reproductive-age females.[1].

While most experience mild to moderate discomfort, and symptoms don't interfere with their personal, social, or professional life, 5% to 8% experience premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and have moderate-to-severe symptoms that can cause significant distress and functional impairment.[2]

PMS and PMDD symptoms can include constipation, diarrhea, bloating or a gassy feeling, breast tenderness, cramping, headache or backache, clumsiness, lower tolerance for noise or light, irritability or hostile behavior, feeling tired, problems sleeping (too much or too little), appetite changes, food cravings, trouble with concentration or memory, tension or anxiety, depression, feelings of sadness, or crying spells, mood swings, and less interest in sex.[3]

It's why this is an important nicotine cessation topic because no one needs to be left behind, including women experiencing PMDD.

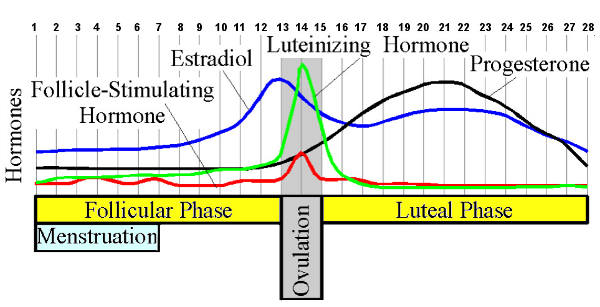

The menstrual cycle can be broken down into two primary segments, the follicular and luteal phases. The follicular phase announces the first day of a woman's cycle, normally lasts 2 weeks, starts with the period of menstrual bleeding, and ends at ovulation.

The luteal phase commences at ovulation, normally lasts two weeks, and ends the day before the next period. The second week is where premenstrual symptoms, if any, are normally encountered.

So here's the often asked question. When is the best time to stop smoking, vaping, or using other nicotine products, during the follicular phase or the luteal phase? Which offers the best odds of success?

The answer may surprise you.

While study findings have been conflicted and mixed, with some finding no difference, some declaring follicular the winner, and others the luteal phase, most had few participants or involved participants toying with NRT or using other chemicals know to stimulate brain neuro-chemicals.

The largest raw study to date was published in 2008, offered counseling only, excluded women using nicotine from sources other than cigarettes, and the findings included 100 percent of the study's original participants (intent-to-treat analysis).

The study's primary aim was to determine whether the menstrual phase during which a woman attempts to stop smoking affects her risk of smoking relapse.

A total of 202 women were randomly assigned to either commence recovery during the luteal phase or the follicular phase. They tracked their menstrual cycle prospectively and were told to either stop smoking between follicular days 4 and 6 or between luteal days 6 and 8. Day 1 was defined as the first day of their period.

The results? After 30 days, 34% of women who started during the luteal phase were still not smoking, compared to only 14% who started during the follicular phase.[4]

Yes, you read that correctly, the luteal phase. The researchers were shocked too. "Our original hypothesis is not supported by the results."

But why? Although poorly understood, is it likely that women already knew how to get as comfortable as possible being temporarily uncomfortable during their premenstrual days?

Withdrawal peaking and beginning to improve within 72 hours of ending use, imagine beginning to feel better and it happening during the luteal phase.

Is it possible that, for some, nicotine withdrawal is actually easier when combined with expected and normal PMS symptoms that may have included varying degrees of irritability, sleep disruption, appetite changes, food cravings, trouble with concentration, tension, anxiety, depression, feelings of sadness, crying spells, or mood swings?

The question now being asked is, is addiction to smoked nicotine a cause of premenstrual syndrome (PMS)? A ten-year study published in 2008 followed 1,057 women who developed PMS and 1,968 reporting no diagnosis of PMS, with only minimal menstrual symptoms.[5]

After adjustment for oral contraceptives and other factors, the authors found that "current smokers were 2.1 times as likely as never-smokers to develop PMS over the next 2-4 years." The study concludes, "Smoking, especially in adolescence and young adulthood, may increase risk of moderate to severe PMS."

When is it best to face challenge? Early on or delay it? As Joel often states, commencing recovery during a period of significant anxiety increases the odds that anxiety will never again serve as an excuse for relapse.

Keep in mind that the smoking woman's subconscious has likely been conditioned to reach for a cigarette during specific menstrual cycle hormonal or symptom related events. But take heart!

The beauty of recovery is that next month's cycle will not be affected by the heightened stresses associated with rapidly declining reserves of the alkaloid nicotine. Also, next month's cycle will likely stand on its own, unaffected by either early withdrawal or cue related crave triggers.

Joel encourages doubters to stroll through the hundreds of thousands of indexed and archived member posts at Freedom, WhyQuit's first cold turkey support group.[6]

"Go back one month and see how many of the women at our site seem to have panicking posts complaining of intense smoking thoughts month after month after month on any kind of regular pattern."

"The fact is, there are no such posts on the board because after the first few months, not smoking becomes a habit, even during times of menstruation."[7]

Joel closes by reminding women concerned about menstrual symptoms, that to keep their recovery on course and getting easier and easier over time, it's still simply a matter of staying totally committed, even during tough times, to their original commitment to Never Take Another Puff!

References:

2. Mishra S, Elliott H, Marwaha R. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 28, 2020.

3. USDHSS, Office on Women's Health, Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), https://www.womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle/premenstrual-syndrome - accessed 09/03/20.

4. Allen SS et al, Menstrual phase effects on smoking relapse, Addiction, May 2008, Volume 103(5), Pages 809-821.

5. Bertone-Johnson ER, et al, Cigarette Smoking and the Development of Premenstrual Syndrome, American Journal of Epidemiology, August 13, 2008.

6. Freedom from Nicotine (support group).

7. Spitzer, J, PMS and Quitting, September 14, 2004, https://whyquit.com/joels-videos/pms-and-quitting/

All rights reserved

Published in the USA