Review: "Quit smoking weapons of mass distraction"

Likely the most critical smoking cessation cross-examination ever.

What if 73% of successful quitters found it "quite easy' or "very easy" to stop smoking, if 41% reported quitting "easier than expected," and if the vast majority who succeeded had quit unassisted, most going cold turkey? If true, why is such inspiring news kept hidden from smokers?

Entitled "Quit Smoking Weapons of Mass Distraction" (link to free PDF copy), a new book by Professor Simon Chapman shouts that quitting on your own isn't nearly as difficult as those pushing approved products, e-cigarettes, and stop smoking programs need and condition smokers to believe.

The underlying theme of Chapman's book is that, although ignored or attacked by nearly all smoking cessation "experts" (mostly ignored), unaided quitting is how most ex-smokers succeed, that the tail has long been wagging the dog.

Imagine the consequences of 80% of smokers believing that quitting is going to be difficult. "Weapons" recounts how, since the '80s, the medicalization of smoking cessation has assaulted free agency, and how individual treatment interventions may have "disempowered people to do things they had long done without help."

And the assault upon the quitter's natural instincts has not been incidental, unintended or honest.

"Don't try to quit cold turkey" campaigns

"Weapons" reviews intentional campaigns to undermine cold turkey quitting. It features a disturbing 2008 UK NHS poster showing a man resisting a taught line tugging on a fishing hook that's penetrating his cheek. The first 2 lines of the caption read, "There are some people who can go cold turkey and stop. But there aren't many of them."

"When I first saw it I was gobsmacked by the outrageously incorrect statement," Chapman writes. "'But there aren't many of them' (who quit cold turkey) is completely and utterly wrong. It's a weapons-grade lie, which as we have seen is easily contradicted by data going back several decades to at least the 1960s."

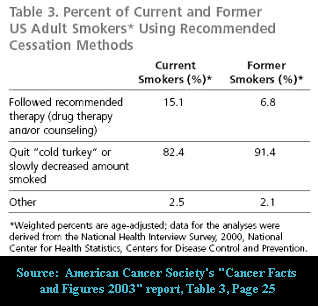

Chapman reviews a number of historic authorities indicating that up to 95.3 percent of smokers had quit unassisted, most by going cold turkey. Among them was the following table from a 2003 National Cancer Institute report indicating that 91.4% of former smokers "Quit 'cold turkey' or slowly decreased the amount smoked."

What struck Professor Chapman was that the 52-page ACS report "astonishingly said nothing whatsoever about this wherever-you-look in-your-face phenomenon." Instead, he notes that 6 pages were devoted to convincing smokers that, if quitting, "you need help."

"When I spot such subversive unassisted quitting figures that seem to have quietly snuck into reports like these almost without comment or discussion, I try to imagine the editorial writing groups who produced them," Chapman writes. "I wonder if they went something like this with the ACS report:"

"Report writer: Are you saying that we should keep it quiet that millions of people have and still do quit unassisted?"

"Chair of writing group: Look, let's acknowledge the data on unassisted quitting, but not dwell on it. I suggest one line in a table or a footnote in small print up the back of the report. Can I see a show of hands? ... Good, done!"

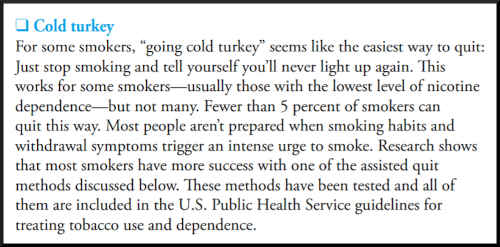

Seeing the NHS "hooked" poster instantly brought to mind page 10 of the U.S. National Cancer Institute booklet entitled "Clearing the Air" which continues to be available for download at both the NCI website and SmokeFree.gov. There, U.S. smokers and quitters are taught the same cold turkey falsehood, that "it works for some smokers ... but not many," that "fewer than 5% of smokers can quit this way."

Imagine having quit smoking cold turkey, being at or near peak withdrawal (24-48 hours) and visiting SmokeFree.gov where cold turkey is not among the 13 listed quitting methods, where typing "cold turkey" into the site's search box returns the message "Your search yielded no results."

And then it happens. You stumble upon "Clearing the Air" where you read the falsehood that quitting cold turkey is nearly impossible, that few succeed.

A government website clearly engineered to sell replacement nicotine while discouraging the world's most productive quitting method, ask yourself, what happens next?

I've long been concerned about the cumulative consequences of telling millions of visiting cold turkey quitters not to attempt spontaneous quitting because quitting "is easier if you have a plan," that they should "pick a quit date," that "NRT can be helpful for dealing with withdrawal and managing cravings," that "almost all smokers can use NRT safely," that "NRT can double your chances of quitting smoking for good."

Cessation evidence lessons

Hundreds and hundreds of smoking cessation studies, many in conflict, how do we make sense of it all?

From evidence not being the "plural of anecdote" to randomized clinical trials, Chapman uses "Weapons of Mass Distraction" to educate readers as to the quality of quitting evidence, including a review of common study biases.

After doing so, he questions the foundation science (blinding integrity) supporting hundreds of highly artificial placebo-controlled quitting product studies, and the theories used to attempt to explain why replacement nicotine (NRT) demonstrates efficacy within randomized trials yet flounders in real-world use.

Product sale and real-world failure defenses laid naked by "Weapons" include the "hardening hypothesis," the transtheoretical theory of behavioral change ("stages of change"), and that quitting unassisted is extremely difficult with few succeeding.

Chapman also exposes the "common liability theory" used to excuse e-cigarettes for addicting "would-be-anyway" teen smokers.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)

NRT for light smokers, pre and post-quit NRT, combination NRT, NRT to prevent relapse, "It appears that there is no smoker, regardless of how much or little they smoke, and regardless of whether they are not at the point of trying to quit, actively trying to do so or have long stopped smoking, for whom medication and especially NRT is not recommended," Chapman writes.

But the nicotine gum, patch, and e-cigs are highly effective, right?

"There can be few if any other drugs, used for any purpose, which have even come close to the dismal success rate of e-cigarettes or NRT in achieving their main outcome," notes Chapman.

"If we went along to a doctor for a health problem and were told, 'Here, take this. It has a 90% failure rate. But let's both agree to call this successful,' we would understandably take the view that 'success' when used in this context was not the way that it is used in any other treatment context."

"It is in the interests of that industry to persuade as many smokers as possible to use pharmaceutical aids for as long as possible."

Chapman uses Australian research to demonstrate that from 1995 to 2006, at the population level, "neither NRT or bupropion nor NRT advertising expenditure had any detectable impact on smoking prevalence."

More recently, he cites a 2013 U.S. Gallup Poll where just 1 in 12 successful quitters credited any approved quitting product for their success.

What's amazing about "Weapons" is how Chapman demolishes the medicalization of smoking cessation with one hand tied behind his back. While "Weapons" includes examples of unassisted or non-NRT quitting being equal or superior in real-world effectiveness, the book's focus rests almost entirely upon ex-smoker productivity.

Not reviewed is the fact that nearly all recent studies examining real-world population-level quitting method effectiveness have found that cold turkey prevails over OTC NRT.

Even the Surgeon General’s 2020 Smoking Cessation Report reluctantly acknowledged that cold turkey generates more successful real-world quitters than all other methods combined and at rates equal or superior to NRT (PDF: see page 15)

So, with few exceptions, why does Chapman's productivity analysis all but ignore quitting method effectiveness?

Because he didn't need to. Because comparing the impact of assisted to unassisted is simple and relatively clean with undeniable results. Because if you ask 1,000 nicotine cessation experts if it's true that the vast majority who successfully arrested their chemical dependence upon nicotine last year did so without resorting to NRT, Zyban, Chantix or Champix, or e-cigarettes, if honest, they have no choice but to say "yes."

Did hundreds of randomized trials dangling free NRT or Chantix as study recruiting bait attract smokers wanting to quit cold turkey? Probably not. Is abrupt cessation twice as effective as gradual weaning schemes? Is spontaneous quitting twice as effective as planned quitting? If our yardstick is nicotine cessation, are smokers who switch to e-cigarettes counted as failures?

Assisted versus unassisted productivity analysis side-steps scores of foundation method comparison issues. Although "Weapons" briefly addresses a number of tangential issues, such as a lack of blinding integrity in placebo-controlled clinical trials, smoking reduction analysis doesn't require it.

It's what makes "Quit smoking weapons of mass distraction" so momentous. It's undeniable that the vast majority of former smokers quit without reliance upon medicalized cessation.

Will pharma and its army of paid consultants counter-attack after being labeled "distractions" or, as with the giant turkey in the room, will they simply pretend it isn't there, that this book was never written?

"Weapons" doesn't just demolish NRT. It attacks those urging a greater need for prescription medications, widespread intensive counseling, support, or e-cig use for "blowing evidence-free and often self-serving smoke."

Champix/Chantix (varenicline)

"Weapons" documents 4.6 million varenicline (Champix) prescriptions written for Australia's roughly 3 million smokers between 2008 and 2020. The obvious question is, given this "staggeringly high level of smoking-cessation pill swallowing" where are the successful varenicline quitters?

Chapman notes that among 11 Australian quantitative studies, between 54% and 78% of ex-smokers quit unassisted.

Professional counseling services

"Weapons of Mass Distraction" reviews the productivity, expense, and worth of telephone quitlines.

Chapman points out that despite massive annual program costs and heavy advertisement, less than 1 in 100 smokers annually contact quitlines, that as few as 1 in 14 callers agree to set a quit date, and that validated quitting among those offered free NRT may actually be substantially less than among those not offered it.

What about the world's most extensive and expensive nationwide clinic quitting programs, the UK's NHS stop smoking services (SSS) where, until it started advocating switching to e-cigarettes, nearly all participants received approved quitting products?

Chapman presents evidence indicating that short-term unverified SSS quitting rates substantially inflate one-year verified rates. While a 2010 study review found an average 15% one-year quitting rate, a 2011 study found a carbon-monoxide validated one-year rate of 6.3% for group counseling and 2.8% for pharmacist support.

Again, although the focus of "Weapons" is on ex-smoker productivity, not effectiveness, Chapman points out that the most commonly referenced one-year rate for unassisted is roughly 5 percent, nearly the same as SSS validated rates. And let's not forget that 5% is after combining all unassisted quitting methods, both effective and ineffective.

He shares 2000 data finding that 58 UK SSS centers averaged 7 employees each, with each center costing taxpayers £214,900 annually, with 54% being spent on NRT and bupropion, and 38% going towards staff costs.

Chapman then notes that a 2005 report found that SSS's overall annual contribution to UK smoking reduction was 0.13 percent per year. This while the vast majority of UK ex-smokers quit unassisted without costing taxpayers a shilling.

E-cigarettes

Exploding since their 2004 introduction in China to a $15 billion (US) worldwide market in 2020, Chapman presents e-cigs as the latest weapon of mass distraction, exposing marketing myths such as vaping being "benign as fairy dust," akin to drinking coffee, "peerless in effectiveness," and able to leap tall buildings.

"Weapons" notes that the PhD "nicotine-is-medicine" industry has megaphoned the message that e-cigarettes are "95% less dangerous" and have the potential to save nearly a billion lives before the century's end.

As for vaping being "95% safer," Chapman notes that this "article of faith" of "vaping theology" was plucked from thin air and that the emperor lacks "evidential clothing." He cautions that while vaping has been widespread for a decade, it took 30-40 years after the invention of cigarette-making machines before tobacco-related diseases started showing up in large numbers.

"Weapons" reminds the PhD industry that "Big Tobacco" is quickly swallowing up the e-cig industry, that its marketing model isn't smoking cessation but simultaneous and mixed use of both cigs and e-cigs, with a substantial percentage of e-cig users engaged in dual use.

Chapman cites evidence that adolescents who had ever used e-cigarettes were 4 to 5 times more likely to start smoking.

He notes how e-cig advocates use the "common liability theory" to explain away the "gateway hypothesis," that "all we need to say about anyone who smokes regularly is that they had a 'propensity' to do so," and that "kids who try stuff, will try stuff," that "kids who smoke, will smoke."

If true, asks Chapman, how do we explain the dramatic decline in youth smoking prior to widespread e-cig use?

As for more than 15,000 e-cig flavorings "Weapons" asks, "why aren't asthma inhalers flavored?" Could it be because inhaling flavorings into the lungs, bloodstream and brain is dangerous and couldn't gain approval?

Chapman notes that while asthma inhaler users are told that it's safe to use their inhaler 4 to 6 times daily, studies have found that the average e-cig user sucks nicotine, flavorings, propylene glycol, and the impurities generated when the cocktail is vaporized by a 300-600 degree Fahrenheit metal coil, 173 to 200 times daily. He contrasts that to the average smoker who inhales 104 puffs per day.

Who is Chapman?

Simon Chapman is a professor emeritus of public health at the University of Sydney. He's editor emeritus of the BMJ journal Tobacco Control where he served as deputy editor from 1992-1997 and editor from 1998-2008.

An author of 535 peer-reviewed journal articles, Chapman is also the father of the plain cigarette packaging movement. In 2013 he was made an Officer of the Order of Australia for his lifetime contributions to public health.

Would Chapman's new book withstand peer review? I suspect it would.

Why WhyQuit?

So, why would WhyQuit, a 23-year-old quitting site that encourages, teaches, and supports cold turkey nicotine dependency recovery feature a book attacking assisted quitting?

Because Chapman is right.

WhyQuit's primary mission has been in countering billions in advertising aimed at getting smokers to replace or substitute nicotine instead of ending its use, a "Weapons" deprogramming voice to encourage smokers to trust in their natural instincts instead of fearing or fighting them.

That being said, close scrutiny of smoking cessation clinic educator Joel Spitzer's life's work -- which has been featured at WhyQuit since 2000 -- supports Chapman's unassisted ex-smoker production message.

In 1985, Chapman authored a Lancet article entitled "Stop-smoking clinics: a case for their abandonment." There, he noted that a "5% success rate among 10,000 people is over 333 times more efficient than the 30% success rate achieved by group work involving only 50 subjects. It is this latter sort of activity, however, that occupies nearly everyone involved in smoking cessation," he wrote.

Joel Spitzer presented 325 two-week, six-session cold turkey stop-smoking clinics involving 4,500 Chicago area participants, and another 690 single-session prevention or cessation seminars to 100,000 attendees. Clearly, Spitzer is one of the world's most accomplished smoking cessation counselors.

Assuming 40% of the 4,500 smokers who attended Spitzer's live cold turkey quitting clinics between 1976 and 2006 broke free for at least one year, that's 1,800 success stories or 60 ex-smokers per year.

We know that a 3-gallon bucket holds roughly 3 million water drops and that, coincidently, roughly 3 million U.S. smokers successfully quit each year. That makes Spitzer's annual average contribution to the bucket just 60 drops. Well, at least until his life's work found its way to the Internet in January 2000.

Over the past 22 years, millions have read one or more of Spitzer's more than 100 quitting articles, downloaded his free ebook (Never Take Another Puff), or watched one or more of his nearly 500 YouTube video lessons.

But, still, Chapman is correct. Smokers generally don't want or need Spitzer's or anyone else's smoking cessation insights. In fact, having myself presented two-week clinics modeled after Joel's, I can attest to the fact that one of life's greatest challenges is convincing smokers to attend quitting programs.

Chapman notes that while "rescuing individuals" one at a time "is nearly always virtuous," that population-wide, mass-reach projects that touch all smokers have far greater potential to inspire widespread quitting.

Both Chapman and Spitzer teach that successful quitting is vastly easier than those selling products and programs want smokers to believe, that there have long been far more ex-smokers than smokers, and that most quit entirely on their own.

Spitzer's core message includes one thing Chapman doesn't. Spitzer accelerates learning of the lesson that's hopefully eventually gleaned from prior failed attempts. It's that nicotine addiction is real drug addiction, that just one puff nearly always leads to full-blown relapse, that lapse equals relapse.

Spitzer shares the solution at the end of every article and video he's ever produced, to Never Take Another Puff! Today, it's a core message being shared at most Internet quitting support sites.

In 2010 I emailed Spitzer a link to a news article about a new Chapman journal article, asking for his thoughts.

The article stated that Chapman had found that smoking cessation clinics were counterproductive in that they send the message that smokers need help and are unlikely to quit on their own, that the vast majority of ex-smokers quit unassisted, and that "mass media campaigns are a better intervention."

Knowing that Spitzer might possibly be the world's record holder for the number of live clinic sessions presented (325 x 6 = 1,950), I was taken by his response.

"Read the article," Spitzer wrote. "I agree with his assessment of the situation. I also believe people have a better chance of quitting on their own than they have by getting the information that they will receive if they do go for live help, which in all likelihood will direct them to pharmacological interventions. So in that way, too, I see clinics as counter-productive."

I replied reminding Spitzer that our online work at WhyQuit was effectively a quitting program and that Chapman didn't appear to be making any exceptions.

"We are not using any funding and we are basically teaching those who find us how to pull off unassisted quitting," Spitzer replied. "If they could get the mass marketing campaign to deliver the message that quitting is doable, and just doing a little mass messaging about addiction, a lot of people will successfully quit smoking. If they could just get the experts out of the field, a lot more people will quit smoking."

"If there were some way to pull all information off the Internet and stop all influence of all experts--meaning all quit boards and public health boards like ACS, Lung, Heart, WHO--all sites that basically push pharmacology-- just wipe the slate clean of all prior information out there, and in the process, we would have to disappear from existence too, or I guess I am saying if none of this ever existed, them or us, well in that alternate universe, there would be a whole lot fewer smokers today than we have now."

"That is the world that kind of existed when I was originally working in this field," Spitzer noted. "The information out there was about the danger of smoking--not really how to quit. The drop in smoking rates during that time period was great. The kind of interventions that are done now stopped that trend. Simon in a way is pointing that out."

"Bottom line though, I believe for the most part Simon is going to be ignored, at least by the experts and most policymakers."

Is Spitzer right, will the core message of "Quit Smoking Weapons of Mass Distraction" be ignored? Actually, it's a topic detailed by Chapman in Chapter 5.

Described as a "major failing" and "appallingly bizarre," Chapman details how prominent quit smoking or nicotine cessation reports have either ignored discussion of how the vast majority succeed or frame it as a "challenge to be eroded by persuading more to use pharmacotherapies," with "zero or negligible reference in reviews and guidelines on how to quit."

It's now been 19 days since the June 25 relase of "Weapons" and this appears to be the book's first public review. Will the most detailed assault ever on smoking cessation continue to be ignored? Stay tuned.

Read "Quit Smoking Weapons of Mass Distraction"

Barnes & Noble (paperback)

Google Play (ebook)

Sidney University Press (paperback)